The image of an empty stadium isn’t as alien these days yet seeing the thousands of blue seats sitting vacant at SDCCU Stadium hits a little different.

Unlike across the country, sports fans in San Diego aren’t looking forward to the day when they’ll be able to return to the once home of the San Diego Padres, Chargers and now San Diego State Aztecs — simply because that day won’t ever come.

The concrete monolith of Mission Valley will slowly be demolished in the coming months, and along with it the physical reminder of over 50 years’ worth of architectural, sporting and entertainment history.

Already, the stadium’s Wikipedia page reads in the past tense, the digital nail in the coffin for a structure that defined San Diego as a sports city and attracted headliners from The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan and Elton John to The Who, One Direction and Beyoncé.

Host to three Super Bowls (’88, ’98 and ’03) and two World Series (’84 and ’98) along with two MLB All-Star Games, two National League Division Series and two National League Championship Series, San Diego Stadium, as it was called upon its completion in 1967, was the only stadium in the United States to host the Super Bowl and World Series in the same year.

It played backdrop to the greatest sportsmen in San Diego history like Don Coryell, Lance Alworth, Tony Gwynn and Trevor Hoffman, among many others.

Yet, the stadium’s illustrious golden years were tarnished by a recent era of neglect and the end of its surreptitious decline was punctuated by the departure of the now-estranged Los Angeles Chargers in 2017.

However, the stadium’s most loyal tenants, the Aztecs, plan to breathe new life into the 135-acre plot on which it stands, albeit not for much longer.

History has a funny way of repeating itself

The inception of SDCCU Stadium, which many instinctively referred to by its former name Qualcomm Stadium, began very similarly to the plans to replace it: a decaying stadium and a ballot measure prompted citizens to think big.

Prior to San Diego Stadium, the Chargers played in Balboa Stadium and the Aztecs in Aztec Bowl. However, both venues left players and fans wanting more, to the point that Chargers owner Barron Hilton threatened to move the franchise to (you guessed it) Los Angeles.

So along came Proposition 1, a city charter amendment that permitted San Diego city officials to issue bonds to build a stadium in Mission Valley. The measure won by a “landslide” The San Diego Union-Tribune (then just The San Diego Union) reported on November 3, 1965, in large part due to the efforts of San Diego Union Sports Editor Jack Murphy for whom, upon his death in 1980, the stadium was renamed.

Murphy saw the potential for a stadium in Mission Valley and starting in 1963 began lobbying support for the development in his columns. Sports reporters of the day say Murphy’s push for a multi-use facility was integral in getting the people to vote in favor of Proposition 1, and overwhelmingly so.

The passion and support for a new stadium in San Diego ran deep.

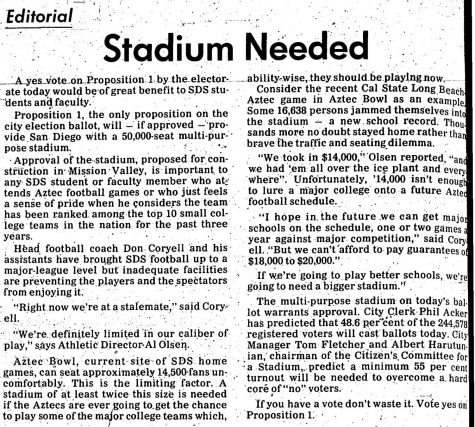

On Nov. 2, 1965, The Daily Aztec Editorial Board wrote in favor of Proposition 1, lamenting that SDS (San Diego State College) would be doomed to be a “small college” football team forever if forced to continue playing at the restrictive Aztec Bowl.

“If we’re going to play better schools, we’re going to need a bigger stadium,” the Board wrote.

The Daily Aztec’s own Sports Editor, Tom Gable, implored voters to empower San Diego and San Diego State to move beyond their bush-league and small college labels.

“For too long we have sat in the shadow of Los Angeles and been content merely to say something should be done,” Gable wrote in 1965. “It is about time we realize San Diego’s potential, accomplish something positive, and make San Diego something more than Tijuana’s northern neighbor.”

However, that zeal for professional sports in San Diego diminished over the years, especially after

the Padres moved into Petco Park in 2004. Efforts to build the Chargers a new $1 billion stadium fizzled out spectacularly and the franchise abandoned San Diego for the City of Angels in January 2017.

the Padres moved into Petco Park in 2004. Efforts to build the Chargers a new $1 billion stadium fizzled out spectacularly and the franchise abandoned San Diego for the City of Angels in January 2017.

In the vacuum left by the Chargers, SDSU, as well as other investors, saw an opportunity to do what the Chargers could not. In 2018, Measure E and Measure G once again tested San Diego voters’ support for the stadium in Mission Valley, and this time they sided with the home team, directing the city of San Diego to initiate the largest real estate deal in its history with SDSU.

The Mission Valley stadium site was sold to SDSU by the city of San Diego on Aug. 7 for $88 million, turning the page in the final chapter of San Diego’s concrete monstrosity.

Saying goodbye to a brutalist beauty

Though a far cry from the modern steel superstructures and glitzy facades of today’s stadiums, SDCCU Stadium was a gem in San Diego’s architectural crown. It was only one of two structures in the city to win a national award from the American Institute of Architects (the other is the Salk Institute for Biological Studies).

Designed by Gary Allen in the brutalist style popularized in the 1950s and 60s, the stadium was groundbreaking in its use of over 1,700 pre-cast concrete forms, some weighing 39 tons. The six spiral pedestrian ramps and the concrete light bands are engineering and construction marvels. The stadium was also home to the world’s longest exterior escalator.

“Things like that, it’s too bad we’re losing the stadium,” architect F. Leeland Hope said. “Even though the sightlines are far from the sidelines, the light band across the top, the circular structures are valuable from an architectural standpoint.”

Leeland Hope’s father Frank Hope Jr. was the principal architect and his uncle Chuck Hope was the structural engineer, both headed up Frank L. Hope Associates a San Diego-based architectural firm started by Leeland Hope’s grandfather, Frank Hope Sr., in 1928.

“I can remember running around on the field when I was 6 years old while the stadium was being built around me,” Leeland Hope said. “This stadium was very much a part of my life growing up.”

SDCCU Stadium was one of the last stadiums in America built by a small local firm and one of the first to be built in the rounded square style, one of Frank Hope Jr.’s largest contributions to the project.

He traveled around the country looking at the way other multi-use stadiums were designed to determine the best way to house both baseball and football, eventually deciding against a circular configuration, Leeland Hope said.

“The circle didn’t convert well, it gave you just a full round outfield and it was not as good for football, so they decided on the rounded square,” he said.

San Diego Stadium was arguably one of the best baseball stadiums built at the time.

However, the stadium San Diegans know today is very different from the one that opened on Aug. 20, 1967.

Back then, the stadium was not entirely enclosed. The area to the left and right of the scoreboard and jumbotron remained open until 1983 when seating capacity was expanded from 50,000 to 59,022 thus enclosing the field. Seats were added again in 1997 bringing the total capacity of the stadium to 67,544.

“At one time it was the best,” Leeland Hope said. “The (1997) expansion made it super good for football but it didn’t work that well with the look of the stadium. They had to get the seats for Spanos.”

Leeland Hope credits his father’s involvement in the construction of the stadium for making him the avid sports fan he is today. Frank Hope Jr. held season tickets for the Padres and Chargers and would bring his son to many of the games.

Of course, designing a stadium for two professional sports franchises came with its perks. Leeland remembers his 10th birthday when his dad flew him to New York City to watch the Chargers take on the Giants at the old Yankee Stadium.

“I got to fly back on the Chargers jet and get everybody’s autograph, and they sang happy birthday to me when the plane landed,” Leeland Hope said.

SDCCU Stadium has special meaning in the Hope family, Leeland Hope said.

“It’s been difficult for my father,” he said. “It’s a bummer, but they say all good things must come to an end.”

However, the stadium currently under construction will pay homage to the giant that came before. SDSU says it will include an exhibit on the history of the Mission Valley and the former stadium and if that isn’t enough Aztec Stadium will literally be built on the bones of its predecessor.

Once demolition is completed in the university’s plans to bury the concrete debris of the old stadium in order to create a platform to build Aztec Stadium on, raising it out of the San Diego River floodplain, Associate Vice President of the SDSU Mission Valley Development Gina Jacobs said.

However, Frank Hope Jr. seemed skeptical the current stadium would be easy (or cheap) to demolish citing the several steel columns drilled down to bedrock. He also said, slightly pleased, he doesn’t think the university will get the permits to bury the old stadium.

However, Frank Hope Jr. made it clear he does not see the demolition of the stadium he built, and that has seated well over a million people, as the end of his legacy.

“It does not make enough sense to worry about it being the end of anything that I’ve ever done,” he said.

A new era follows the end of an old one

The demise of SDCCU Stadium is bittersweet. It’s sobering to see the concrete that has largely stood the test of time begin to come down. Yet, even more, sobering is the fact that a generation of San Diegans will never have the opportunity to experience the stadium on gameday, walk on those round ramps and ride the escalator that seemed to go on for ages.

For SDSU freshmen, like Genevieve Hope, Frank Hope Jr.’s granddaughter, the first Aztec football game they will attend as students will be in a new stadium.

However, much like the vision presented to San Diegans by Jack Murphy in 1965, the vision of a new stadium in Mission Valley along with a state-of-the-art research campus, river park and residential development is one that excites. Though many wish they could sit in the seats at SDCCU Stadium one last time, broken cupholders and all.