A breeze blows through the leaves near San Diego State University’s Turtle Pond as I sit across from poet and fourth year English major Nico Demers with a copy of his newly released poetry collection, “Belly,” in my hands. The peaceful, almost pastoral setting serves as a fitting backdrop for our discussion of his work.

A collection of three chapters that offer meditations on love, family, the body and the violent beauty that runs through each, Demers’ work features frequent references to nature as a metaphor for both the self and the transcendent. Before the poems even begin, the collection is dedicated to the ocean.

“Yes, it’s dedicated to the literal ocean, but I’ve always considered my house an ocean, my life an ocean, the love that I’m experiencing an ocean,” Demers said.

This dedication is a beautiful introduction to the first section of poems, “Mirror,” which blissfully describes the religious nature of young love. In perhaps his most well-known poem, “I am a Catholic,” Demers writes: “I nailed my hands on her hips like they were a cross / At night, / I kneel at my bedside and pray to my God / that looks just like her. / I am religiously in love.”

The following chapter explores the relationship between religion and love, begging to argue that the two may be the same.

“Love is absolutely a religion in the way you devote yourself to it, the way you practice it and the way you constantly come to it in times of desperation and in times of happiness,” Demers said.

“Mirror” paints a picture that matches this theme: the transcendence of the body through love. Demers explores his spirituality in conjunction with his love and affection for his girlfriend, Quinnie, through the body — one of the collection’s most prevalent symbols.

“In every piece of religion and almost every piece of literature, there’s a constant obsession with the body,” Demers said. “It’s the one persistent thing in your life. And with that persistence comes hating your body, loving your body, touching another body, wanting to escape the body or come back to your body. So it’s the one thing that we can’t get rid of, and it’s this one thing that’s always going to be with us.”

The second section, “Tree,” moves into work that is much thornier, with Demers calling it the “most painfully cathartic part of the book to write.”

The catharsis of the section is jarring, as Demers digs into childhood trauma, switching between adult remembrance of the pain and child-like first-person retellings of events before landing on a mature acceptance and forgiveness.

“Tree” painfully delves into the memories of Demers’ parents’ divorce, as he writes in the poem “Molding:” “I hate looking through old things. / It makes me feel again. / It makes my limbs shake.” This line encapsulates the theme of the entire second section: the pain of looking back over memories we would prefer to forget.

“Tree” builds upon the metaphor of nature of the first section, transforming the idyllic love poems into a sobering look at the death and decay inherent in all things natural. In a line that is sure to leap out at readers, Demers writes, “And I already know when I do get married / I am probably going to get divorced.”

After reading nearly 40 pages about Demers’ love for the subject of Mirror, it can shock the reader to see this sort of line.

“Tree is supposed to be the signifier of my progression from childhood to adulthood,” Demers said. “I wanted to throw in these moments where I had these darker thoughts — where suddenly — I started thinking love isn’t always this beautiful, happy thing.”

The collection closes with a section entitled “Cut.” The poems continue the theme of the body as transcendent but complicate the emotions by including the spirituality in eating disorders, according to Demers.

The poems of this section are shocking for their unguarded vulnerability and emotional intensity.

“When you have that horrible relationship with food, the religious part is starving yourself,” Demers said. “So, in the same way that you’re religiously in love and you devote your all to it, you’re religiously starving.”

In the poem “Weight-ins,” Demers writes, “I wake up mornings limping back to the scale like a / church. / I mount my feet on it like a cross and worship my / weight.”

After sections describing romantic love and exploring childhood trauma, the final section of “Belly” is perfectly unpolished in its depiction of ongoing hardships. Demers reminds readers that there is beauty and pain in all things, but through the confusion comes transcendence. “Cut” concludes the collection masterfully by bringing the theme of the body full circle.

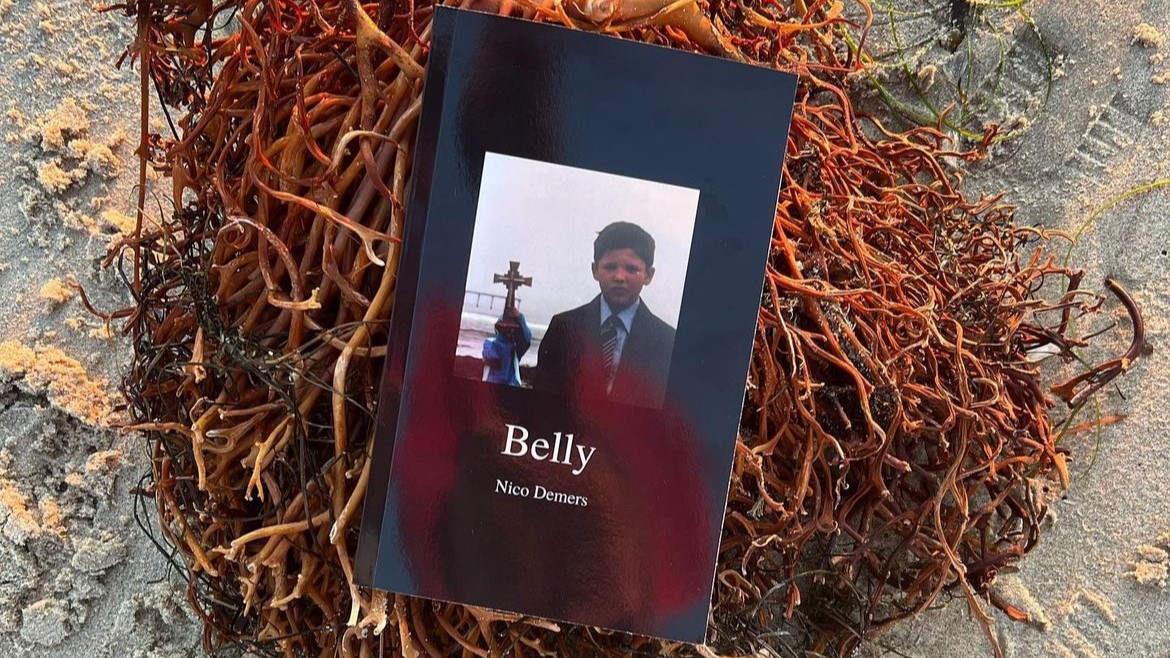

The cover of “Belly” features a photograph of Demers as a child, frowning on his way to his first communion. Behind him lies a crucifix and the Pacific Ocean, beautifully encompassing the themes and messages that lie within the collection.

“So the body is sort of the ribbon tied around the entire collection?” I asked Demers.

“Yeah,” he smiled. “Yeah, it is.”