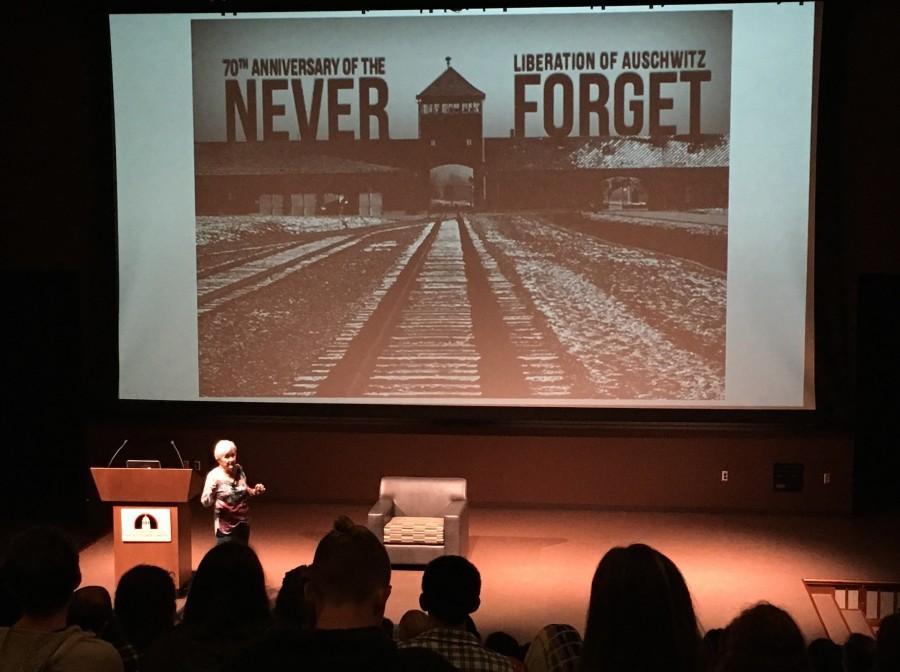

Holocaust survivor Rose Schwartz Schindler touched the hearts of San Diego State students on Thursday, March 3 in the Conrad Prebys Aztec Student Union theater as she shared her life story from the time she and her family were taken to a concentration camp to present day.

The One SDSU Community teamed up with Anti-Defamation League to host the event as part of “Week of Caring.”

“I think that these events are really important,” said Cassi Grunder, assistant regional director of ADL. “It’s important for students to seek out this kind of information to inform their studies and their lives.”

Schindler was born in 1929 in Seredne, a town with only about 2,000 people in what is now known as the Czech Republic. She grew up with her parents, aunt and seven brothers and sisters all under one roof.

In 1938, Hungary took over Seredne by shutting down Jewish businesses, banning children from schools and putting restrictions on the residents of Seredne.

“It was like being in a jail. We were not allowed to leave town without permission,” Schindler said.

In the spring of 1944, Schindler came home to her mother telling her she needed to pack because they were going away.

Schindler recalled a specific moment before leaving when her father told her to put her jewelry in a small box. He hid it in a small corner between the ceiling and the wall.

She and her family were then put on a train for days without bathrooms or water.

“The stench in the train was pretty bad,” Schindler said. “People had to relieve themselves.”

Schindler said when she arrived at the Auschwitz concentration camp, a man in a striped uniform asked her how old she was, and she said 14. The man told her to lie and say 18.

Because of this, Schindler was put in the line with her two older sisters instead of the line with her mother and her four younger siblings who would be sent to the gas chamber.

She never saw them again.

Schindler and her sisters were stripped and shaved down and given a rag to wear. Her rag was too long, so she cut a piece off and put it around her head to keep warm.

She said that out of curiosity, she went outside to see what was happening and saw hundreds of dead bodies.

Her father then came to see her before being sent to a working camp with her brother. He told Schindler to “stay alive, so (she) can tell the world what they did to (them).”

Schindler said she and her sisters met up with her father and brother the next day to say goodbye, and that was the last time she saw them.

She and her sisters stayed at the Auschwitz concentration camp for three to four months in poor conditions and with minimal food.

“We were treated like we weren’t even there,” she said. “We were treated worse than bugs in the ground.”

They then decided it was time for them to get selected to work in better conditions in order for them to survive.

However, Schindler said she was “skin and bone” and there was no way for her to be selected.

Around September 1944, 200 women were needed to work in a factory. Schindler told her sisters to try to get selected and she would find a way to sneak into the transport line.

She was able to sneak in while her sisters held a place for her in line, escaping the setting and conditions of Auschwitz.

At this factory, Schindler and her sisters were disinfected, shaved and given proper clothing. They also had mattresses and sleeping bags.

“It was going from hell to heaven,” she said.

Schindler worked on gas masks at this factory for about eight months and in May 1945, she and the rest of the women were getting ready to be picked up to go to the factory, but none of the German soldiers showed up.

She said she told her sisters she was going outside to see what was going on and then saw that all the soldiers had run away.

“The gate was wide open,” Schindler said. “I’m free.”

She said she heard the Russian language and gunshots and saw planes flying above her head, so she grabbed a rag, put it on a stick and ran to a corn field to wave it around as a sign of peace.

The Russians liberated her and all 200 women that day.

“I felt I was reborn,” Schindler said. “I was like a new person. I am free and can do what I want.”

She and her sisters went back to Seredne and found the box where her family had stored their jewelry. To this day, Schindler still wears the necklace from her father’s pocketwatch.

She spent time in orphanages after and met her husband, another Holocaust survivor, in one of them.

They moved to San Diego in 1956 and have been living there since then. They have four children and nine grandchildren, one who attends SDSU.

“I want to speak because I want the rest of world to know what we went through,” Schindler said.

Her words reached the hearts of many students, and she reminded them to be thankful for the place they live in now.

“I thought it was pretty incredible she could share all that, stay composed and just share such a horrific story with everyone,” said Dominic Gialdini, a freshman international business and recreation and tourism management double major. “I’m glad she did.”

Schindler’s story was part of the “Week of Caring” series, but event organizers believe the week’s events will stay with them for much longer than a week.

“I think that this kind of work is really important for helping students create the kind of campus climate they want,” Grunder said.