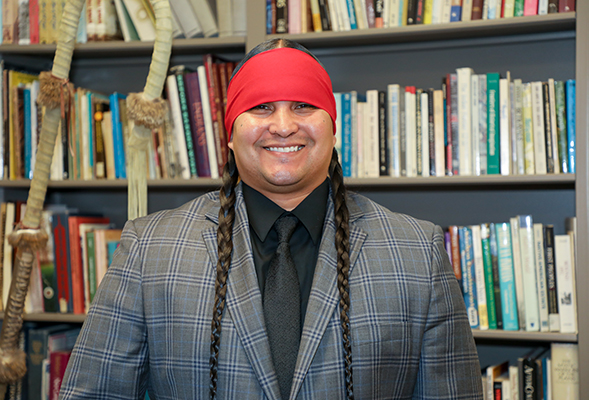

When Jacob Alvarado Waipuk graduated from San Diego State in 2014, he knew he would go on to make a difference in his community. What he didn’t know was that he would soon become the university’s first ever Tribal Liaison.

After graduating from SDSU with a degree in American Indian studies, Alvarado — a member of the Kumeyaay nation — began teaching an American Indian studies course and collaborating with local tribes. Now, he said he hopes to use his new position to continue this work and create more change in the university system.

“I want to enhance American Indian educational pathways and opportunities, advance tribal connections and partnerships, increase American Indian representation and recognition and increase recruitment, retention and graduation (of Native students),” he said.

Alvarado said he also wants to create a curriculum that educates students, faculty and staff on the history of the Kumeyaay nation and bring experts of Kumeyaay history onto campus.

Serving as SDSU’s Tribal Liaison is Alvarado’s way of giving back to his people.

“I’ve always been an advocate for my people,” he said. “I grew up with Kumeyaay traditions and culture. It was instilled at a young age to always give back to your people.”

The rich history of the Kumeyaay nation is often buried, literally and figuratively, beneath newer establishments such as the university. Alvarado said he hopes to bring more awareness to the hidden history and culture of the Kumeyaay people.

“When you lift up all this stuff, there’s villages that were here, the Kumeyaay nation’s stories are here, our way of life is here and the story of our people is here,” he said. “We need to bring awareness by getting everyone to know who we are as Kumeyaay people, to hear our story and understand where we’re at.”

Alvarado said since he has accepted his new position, he now has a place on multiple university government councils including the Inclusion Council, the Equity Council and the Senate Council. Along with university-centered work, Alvarado said he also works with tribes in the area to build more collaborative relationships.

One of the biggest problems Native people face, according to Alvarado, is a mistrust of institutions like universities. He said because of the history of westernization through boarding schools and destructions of culture, Native people are still working to heal within these institutions. He added that the university’s acknowledgment of the land SDSU resides on as Kumeyaay land, as well as the creation of his position, were huge steps forward in building and healing those relationships with local tribes.

Professor of American Indian Studies and Undergraduate Advisor Margaret Field said there was need for a Tribal Liaison because of the work the university and its students do with tribal communities.

“We need one because there are various programs that interface with tribal communities on campus,” she said.

Associate Professor of American Indian Studies and Department Chair David Kamper said the creation of the Tribal Liaison position was long overdue.

“Several universities across the country have had this position for years and in the county of San Diego we are the last major university to do this, which is a little disappointing but we’re rectifying that,” he said.

Kamper described the liaison position as a bridge between SDSU and local tribes. He added that Alvarado was perfect for the role because of his deep understanding of the Native community and of SDSU.