There are more than a handful of monotonous music documentaries. “The Boy From Medellín” is not one of them.

With a protagonist that has doubts and dreams worth exploring, “The Boy From Medellín” is one of the few docs pinpointing a single moment in a musician’s life that was worth making into a movie. I’m not speaking of films that recount tragic musical events (“Gimme Shelter”), cinematic chronicles of an eventful life (“Amy,” “Everybody’s Everything”) or even lavish home-concert transplants (“Homecoming,” “Amazing Grace”). I’m referencing the documentaries that place you into an artist’s daily routine as they’re about to embark on a big tour, concert or new creative venture.

These films often have celebrity cameos, massive fan service, and provide brief glimpses of backstage life and tidbits about an artist’s habits and mindset, without offering anything worth the price of admission or a Netflix subscription. Backstage access is cool, so are concert close-ups and tagging along with artists on their errands, though it gets stale after seeing them for the 50th time.

One of the more recent entries of this sub-genre is “Ariana Grande: Excuse Me, I Love You.” I admire the personality, artistry and strength of Grande, but her doc didn’t really offer anything unique. There was a lot of behind-the-scenes footage, similar to what she already uploads on YouTube, and much of the doc spends time alternating between going back and forth between a traditional concert film and a celebrity vlog.

Oftentimes the subjects in these “concert docs” either aren’t interesting enough to document or whatever their doing isn’t out of the ordinary. In Grande’s case, the filmmakers failed to capitalize on limitless story potential, and this film variant only thrives when deviating from the script.

Reggaeton, a melodic sing-rap combination primarily performed in Spanish with influence spanning from Caribbean dancehall to hip-hop is one of the world’s most popular musical forms and has found a lasting audience among English-speaking listeners. Let me quickly remind you of the exorbitant prices some concertgoers have been paying for tickets to see Bad Bunny perform in San Diego because if that’s not enduring popularity, then I don’t know what is.

At the forefront of this Latinx music movement, along with Bad Bunny, and his Puerto Rican collaborators Ozuna and Nicky Jam, is J Balvin. As the “Prince of Reggaeton,” J Balvin is helping expand the artistry that first began in Puerto Rico during the mid-1990s and is the leader of Colombia’s recent rap surge. He also dabbles in latin trap, a companion genre to reggaeton influenced by southern trap, following the original imprint made by artists like Daddy Yankee, the most popular example being Cardi B’s “I Like It,” featuring Balvin and Bad Bunny.

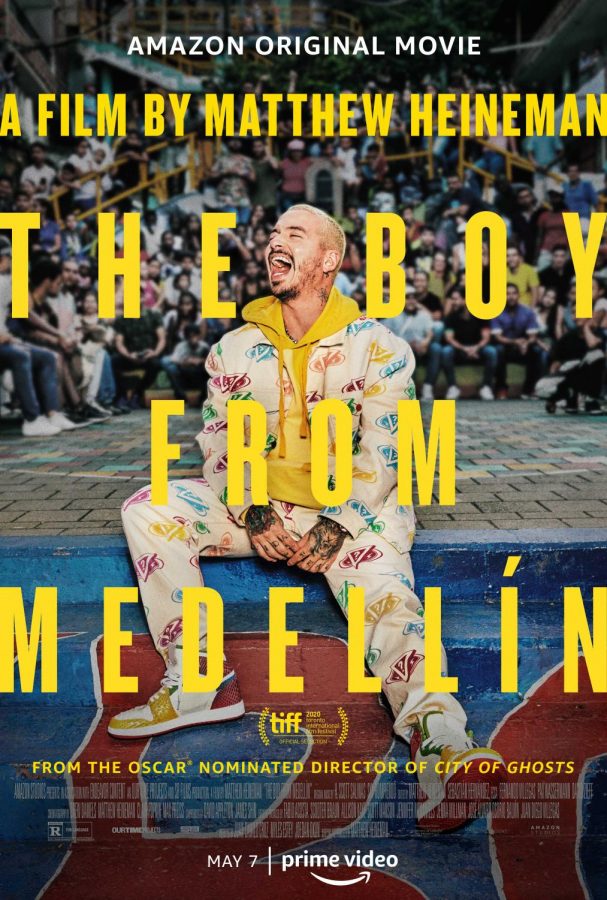

As the second artist to be given an exclusive meal from McDonald’s (after Travis Scott), the first reggaeton artist to perform on “Saturday Night Live” and the most nominated artist of 2018 Latin Grammys, where he won Best Urban Music Album for “Vibras,” J Balvin has put together a distinct resume. Now, “The Boy From Medellín” has his own documentary to boot.

Shot over the course of one week in the life of José Álvaro Osorio Balvín, filming took place in November 2019, with the natural backdrop being the testy social climate of Colombia amid economic and social protests in favor of greater access to education aimed at President Iván Duque Márquez. His life story up to that point is glued together with grainy homemade footage to document his musical rise as J Balvin. From throwing a completely empty concert to his time painting houses as a side gig in Miami, Balvin never wants anyone (including himself) to forget how he earned his path or diminish his impact.

Upon returning from a massive concert in Mexico, there’s a mountain of hype leading up to Balvin’s first hometown headlining show at Atanasio Girardot Stadium on November 30th. From there, Balvin tries to determine what his true role is as an artist and whether he should speak first as a citizen or musician when addressing social problems.

Among increasing protests, Balvin’s concert is positioned as an event that could ease the strife of Colombia, or at least provide enough peace for one night. Making clear his aversion to politics, he says “We will have a humanitarian moment, not a political one.” For Balvin, this concert is the ultimate homecoming and the only goal he’s yet to accomplish, and when he returns from tour to crowds of waving fans and endless smiles it’s like a king returning to his castle. If he has a choice in the matter, Balvin doesn’t want this event to be spoiled by anything.

Right away, the audience is placed within Balvin’s inner circle in his luscious home among spiritual guides, nutritionists, assistants, family and friends preparing him for his biggest show yet. Inserting itself as the primary focus of the story is the looming presence of civil unrest in Colombia.

The possibility of the concert being postponed gets floated around with radio reports describing worker strikes, news footage of protestors marching across the screen and concert cancellations piling up around the country. (It’s imminent the concert will happen, because why else would a film be made, but it’s convincing enough to make viewers really think it won’t happen.)

While preparing for the fateful week, Balvin opens up about his mental health struggles, recalling a sensation he felt during a concert in Puerto Rico and saying “it’s hell for real” where everything in his mind is terrorizing him. There are times when he’s unable to separate himself from his identity as J Balvin, his artistic, playboy alter ego. At the height of his troubles in 2016, he was canceling gigs and landed in the hospital due to “extreme exhaustion.” Since then he’s formed a public platform advocating for those sharing similar experiences with anxiety and depression.

With the pressure he’s put on himself to uplift his family and change the image of Medellin that was tarnished by Pablo Escobar and the mythology of drug lords, Balvin has always been aspirational.

When he first left Colombia to jumpstart his musical ambitions he worried about shamefully coming home as a loser, and this is when his depression first emerged. When Balvin did return, he didn’t give up on his dreams. Balvin began performing all over the city in random locations and built up a local fanbase that would expand worldwide.

His music made him a Colombian folk hero and his personal revelations about depression have left a tremendously positive impact, but the single thing he never pictured himself being was an activist.

Every time he tried to insert himself in the protests it backfired. Whether it was his comments in Mexico where he claimed “I’m not on the left or the right, but I’m always walking forward with dignity and respect.” His ill-timed and insensitive Instagram post referencing the death of Dilan Cruz, a Colombian teenager who died two days after being struck in the head by a police projectile during the protests. Or an interview with a local journalist where he gets annoyed at the prospect of criticism whether or not he speaks out and says “our work is to entertain” as a performer.

Balvin’s frustration at the prospect of saying the wrong thing and receiving neverending backlash is equally countered by his circle around him pleading him to stay apolitical and looking to protect his image.

Colombians who value his perspective were left waiting on a proper response that kept getting endlessly delayed, only angering them further and ensuring Balvin dug himself an increasingly deeper hole. Rising Colombian rap duo Doble Porción criticized Balvin for not speaking up on political topics and fans hit back at him for making an acknowledgment of Cruz’s death without mentioning the circumstances in which he died.

Throughout the week, Balvin bounces his grievances off everyone. The mayor of Medellin, his girlfriend, former Miss Argentina Valentina Ferrer (who he’s now expecting a child with), his parents, even the camera. He wants to be loved, adored, accepted all while still following his dreams and staying within himself as both a person and public figure.

Speaking with younger artists in the area helped Balvin connect better with the issues at hand and shockingly out of the many people he spoke with while searching for advice, infamous manager of the stars Scooter Braun put things in perspective best.

“J Balvin has a platform, José is the one who needs to speak.”

It’s always easy to predict the type of decision Balvin’s going to make, but it doesn’t make the payoff any less satisfying or climactic. It’s fascinating, like watching a real-world ethical dilemma problem play out on screen.

Balvin’s experiences offer fair insight into the added social responsibility that celebrities are entrusted with by the public. His journey is intriguing and at times even captivating with an exquisite balance of on-stage and backstage focus. You really get to know who he is, what he values, without his actions becoming camp.

8/10