In 2017, “Coco” popularized Día de Muertos across the world. “Coco” was a small step forward, broadening the public perspective of what Mexican culture is about. Although heartwarming, there are many aspects of the cultural significance of Día de Muertos in Mexico the film fails to capture.

The holiday originated in Mexico, where it remains an important celebration, but is celebrated across Latin America. One of the most common misunderstandings surrounding this celebration pertains to the name itself. This day has come to be internationally known as “Día de los Muertos.” Although grammatically correct in Spanish, it is worth mentioning that the traditional name in Mexico is “Día de Muertos.”

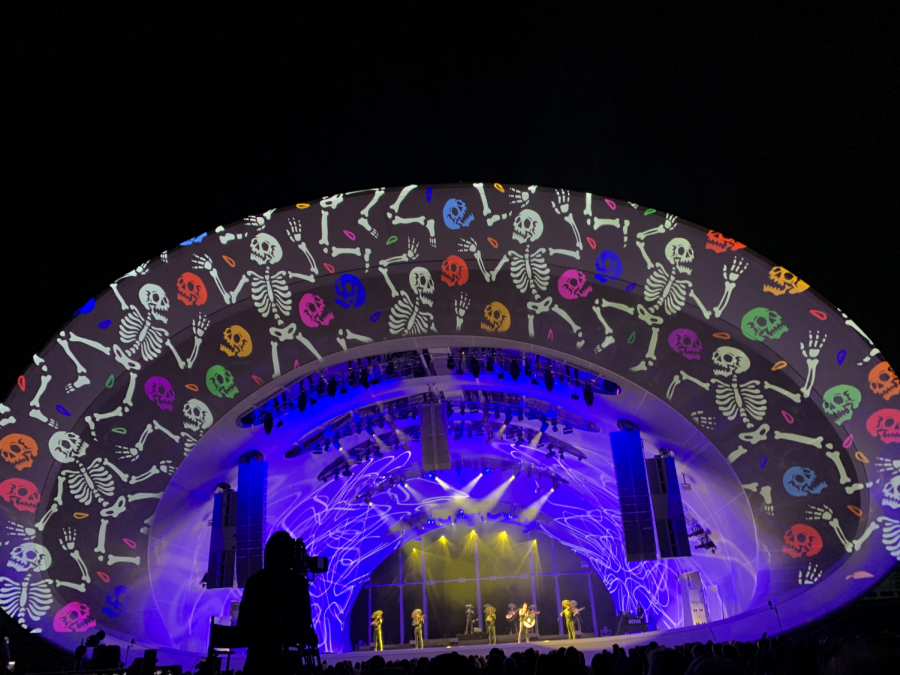

To commemorate Día De Muertos, Ballet Folclórico de Los Ángeles and Mariachi Garibaldi Jaime Cuéllar shared the stage at the Rady Shell in a celebration titled “Ofrenda” (offering) on Oct. 31.

From the beginning, “Ofrenda” painted a broad picture of what being Mexican is about. The event started with Mariachi Garibaldi singing “a capella.” Soon enough, the ensemble joined the singer and the dancers entered the stage, dressed as “adelitas” (revolutionary women) and “charros” (traditional horsemen).

The dancers wore colorful dresses that captured various Mexican traditions of different states, and the songs performed successfully portrayed the cultural diversity that exists within Mexico.

A staple of any Mexican folklore celebration, the ballet performed the traditional song from Veracruz, “La Bruja.” For this song, the dancers place a lit candle on their heads, and dance while keeping this steady to prevent it from falling.

The ballet’s creativity was beautifully captured throughout the performance.In “La Feria de San Marcos,” a song about a rooster fight, two dancers wearing red and orange capes represented the roosters, and their choreography captured the fight as both jumped at one another and spun around.

Eventually, and in time with the lyrics, one of the roosters wins. The audience watches some of the dancers pickup the losing rooster and carry him off-stage, as the winning party is celebrated.

Even with dancers constantly making their way across the stage, they showcased their innovative spirit by finding a way to include the altar by having the dancers roll one out during the last performance. At this point, the altar became the anchor for the dancers. They drew closer to the altar, seemingly showing it respect with everything about their bodies and demeanor.

A significant part of this immortal worldview is the perpetually youthful spirit that many Mexicans share. Even as one ages, we continue to be young at heart, with dances like “El baile del anciano” (The Old Man’s Dance) capturing this energetic spirit, passionately hopeful for the future and whatever it holds, including death.

Some of the featured songs helped capture these perspectives. Lyrics such as “For me, life is a dream, and death the awakening,” and “Don’t mourn me, for no one is eternal” capture the care-free, calm attitude of being Mexican, even when it comes to death.

The most common misunderstanding surrounding Día de Muertos is about what is being celebrated. On this day, we remember our ancestors and family members that have passed, and hope they have found their way into a peaceful afterlife. It has little to do with death itself, and is mostly about community. For these communities, Día de Muertos has an important role in their identity and worldview (Instituto Nacional de las Lenguas Indígenas).

That being said, these Mexican communities often have a peculiar attitude surrounding the rather grim subject of death. “Ofrenda” aptly captured not only what the celebration of Día de Muertos is about, but succinctly portrayed the multitudes of what life and death mean in Mexico.