Much like the human body, as the heart gets older it loses the ability to repair itself.

This is often what’s behind chronic heart disease. As the heart repeatedly tries and fails to repair itself after an injury, such as a heart attack, it increases the likelihood of heart failure in the future.

The persistent problem is one reason why heart disease is the leading cause of death for both men and women and is responsible for about 600,000 deaths each year in the U.S. alone, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

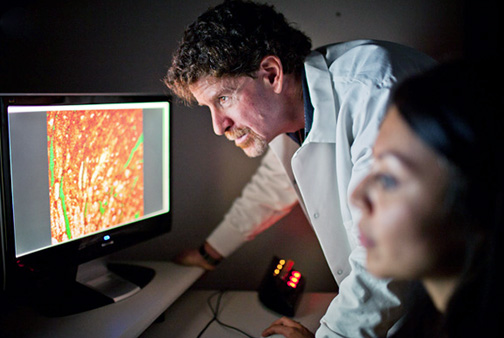

Now, researchers at the San Diego State Heart Institute are trying to break the cycle by approaching it on a cellular level. It is doing it with a recently awarded grant for $8.5 million from the National Institutes of Health, vaulting the university into the top tier of research institutions around the country.

The project grant, led by the director of SDSU’s Integrated Regenerative Research Institute, Dr. Mark Sussman, is a collaboration between researchers at SDSU and University of California, San Diego. The research is divided into four components, each supervised by its own principal investigator. The SDSU team includes Sussman and Director of the SDSU Heart Institute Dr. Christopher Glembotski, with UCSD’s Dr. Joan Heller Brown and Dr. Asa Gustafsson.

The research also is a teaching lab for many undergraduate and graduate students.

“The people who are doing much of the heavy lifting are students here at SDSU,” Sussman said.

The research is building on work done with a previous project grant from the NIH awarded in 2006 by riding the new wave of interest in stem cells as a remedy for disease.

“Up until fairly recently, we really didn’t understand that the heart had the ability to repair itself,” Sussman said.

He added that unfortunately the heart is somewhat of an underachiever when it comes to repairing itself.

Glembotski explained that like other parts of the body, when the heart is damaged, it attempts to repair itself by forming scar tissue, replacing vital muscle tissue the heart needs to function.

“One of the overarching goals that we have is how to get the heart to rebuild the muscle tissue that was once there before it got damaged,” Glembotski said.

The answer may lie in stem cells, the cells that morph into new tissue. Researchers think that as people get older, so do their stem cells, inhibiting their regenerative role in the body.

Another part of the research involves understanding the environment of the heart, which can affect how stem cells communicate, research fellow Shirin Doroudgar, who received her Ph.D. last year in a joint-doctoral program of SDSU and UCSD, said.

“Understanding the environment of the heart and the proteins that make up the environment of the heart outside of the cells are important for how stem cells talk to each other or talk to the cardiac muscle cells,” Doroudgar said. “And once we understand that, we hope that we can change the environment of the heart in an older individual patient or model system to mimic a younger individual.”

The grant will fund the work of the researchers for the next five years.

“It’s not beyond the realm of possibility that we could find such a youth drug, as it were, for the heart or for other organs too,” Glembotski said.

Photo courtesy of NewsCenter