From posting suicide notes to showcasing what you had for lunch, social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter have transformed our patterns of behavior. We see posts everyday that chronicle and often glamorize events and thoughts that are sometimes trivial. What compels someone to share with hundreds of people their thoughts and publish what used to be intimate glimpses into their lives?

A 2012 Harvard study shows that talking about oneself causes significant activity in the NAcc and VTA regions of the brain, which are associated with reward processing. The idea that talking about oneself is inherently rewarding is probably not earth-shattering to most people, but it has important implications regarding the way we use social media.

I opened Facebook recently and saw someone’s post that read, “Try not to confuse being ambitious with being entitled,” followed by some likes and comments. But I wonder, with social media aren’t we all “entitled” to an audience? Human nature grants us a certain amount of ambition to strive for socially constructed heroics, or what to many people is fame. The desire for fame is not limited to 13-year-old girls with Bieber fever. It’s embedded in all of us.

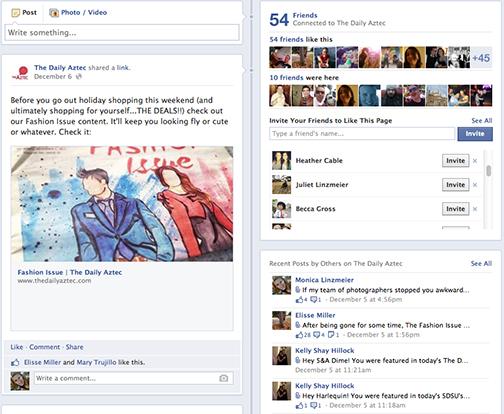

According to assistant professor of psychology Dara Greenwood at Vassar College, fame manifests itself in three different ways: visibility, status and prosocial, the ability to support a family or use fame to support a cause. Social media perpetuates all three. The ability to include actual celebrities in one’s online social circle is a huge step toward encouraging the fame-driven ego, along with the ability to have a large audience to provide feedback in such forms as likes, comments and followings.

The reason we should be cautious of how actively we use social media platforms (passive reading does not necessarily apply to the same extent) is that some of our most important interactions are face-to-face–the first date, the job interview, familial relations. There has been a lot of buzz surrounding the virtual persona, or the way people present themselves through social media. In this sense, this persona is often a version filtered to highlight a person’s more desirable or fame-provoking aspects. It becomes dangerous when the user is so frequently active that he or she is not fully conscious of the difference between online and offline personas. The extension of social media to our mobile devices further blurs these lines, because it means our more desirable persona is always with us, an audience of hundreds is in our pocket.

Social media platforms are set up to make fame accessible to everyone. When we publish on these platforms, we are rarely ignored or rejected, so our online behavioral systems almost always generate a positive or encouraging response. Herein lie the damaging effects of Facebook on the ego. The important interactions in the real world will be cast aside by the less socially gifted in favor of constructing an attractive online persona featuring an absence of judgmental audience members, but with hundreds of “friends” who are posed to give positive or at least engaging feedback.

Not everyone is prone to give his or her fallible self up for a well-crafted ideal, and many people still crave the heat of face-to-face interaction. However, a new generation is emerging that has begun to shape its fame-driven personas at a young age, and I’m anxious to see what effects this will have on their psychological development. As for the rest of us, let’s try to keep ourselves humble in the reality of physical human interaction while the practice still exists. When that becomes outdated, we may spend our days reveling in the virtual world where fame is but a click away.