February is always a reflective month for me. Not only is it the month that my workload for the new semester starts to speed up and it’s my birthday month, where I reflect on the age I’m about to turn. It’s also the month dedicated to celebrating people whom I share a racial identity with. I’m talking about Black History Month.

Every February, children in elementary school learn about famous African-American heroes, such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Harriet Tubman. They hear stories about the underground railroads and listen to the speech “I Have a Dream”.

Teachers dust off their history notes and give students information about African-American inventors, writers and artists. The month of February, in its 28 days of glory, also brings light to African-Americans who aren’t as well-known.

Although I’m adamant about celebrating culture and embracing ethnicity, this year I felt indifferent about the holiday. I have found myself conflicted about the idea of celebrating black history, and on the other end of the spectrum wondered why such a holiday would need to take place in 2014.

Black History Month reminds African-Americans, along with other Americans, that Black people are still different from the American population and because of that, should have their own holiday.

I can recall times in my life when my blackness became a significant factor in situations when it shouldn’t have.

For example, when associates or friends have labeled me as their “black friend” rather than just their friend, or when any word has preceded the statement, “for a black girl” have followed.

When Martin Luther King, Jr. made his famous speech and spoke words of hope for his children to be judged on the content of their character, not the color of their skin, I believe he intended for Americans to view their fellow citizens as people of the same nationality versus emphasizing on their hyphenated ethnicities.

The U.S. is becoming more interracial as the years go by. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, there has been a 134 percent increase from 2000 to 2010 of half black/half white children and 9 million people have stated that they are of mixed ethnicity.

Out of these mixed people, 1.8 million identify black and white. That number has made a huge jump since the 2000 census and I’m sure the number will only grow in the 2020 census.

The younger generations of children are now accustomed to having classmates of different ethnicities, or at least being exposed to them in the media. As for millennials, especially at San Diego State, most know someone in an interracial relationship or have a friend of another ethnicity.

As a history nerd, I understand the importance of history. African-Americans have existed in this country, enslaved and free, for as long as our Founding Fathers have been around. Black history is American history, but it isn’t being portrayed that way.

History teachers should incorporate black history into periodical topics, 365 days a year.

Historians could definitely bring more light upon African-Americans, such as Crispus Attucks, who was the first casualty of the Boston Masscare revolutionary protest in 1770.

There should be a truth to the history focusing on the good (MLK), the bad (the

highly-controversial Malcolm X) and even the ugly, like the violent deaths of Emmett

Till and Medgar Evers.

I love the idea of celebrating black excellence. It’s the “history” part that gets me.

If African-American history was prominent in history classes year-round, then Black History Month could have a whole different meaning. Because African-Americans are so far removed from their African roots, it would be hard to relate to Africa’s traditions. But with many black references in American culture, such as jazz music, soul food and artwork from the Harlem Renaissance, there’s much to celebrate.

America should take time to celebrate current or up-and-coming prominent African-Americans.

During the month of February, Americans can try to focus on current issues of African-Americans, such as finding a solution as to why African-Americans remain the most impoverished ethnicity in our country.

Although we now have an African-American president, and the mayor of New York is in an interracial marriage with biracial children, we also have had many setbacks, such as the Trayvon Martin case.

Education is the way to inform people about history and continue the education of what we have learned that doesn’t work in the past. With the education of black history consistently fused into history, together we can work to create MLK’s dream and celebrate being American and not just our race.

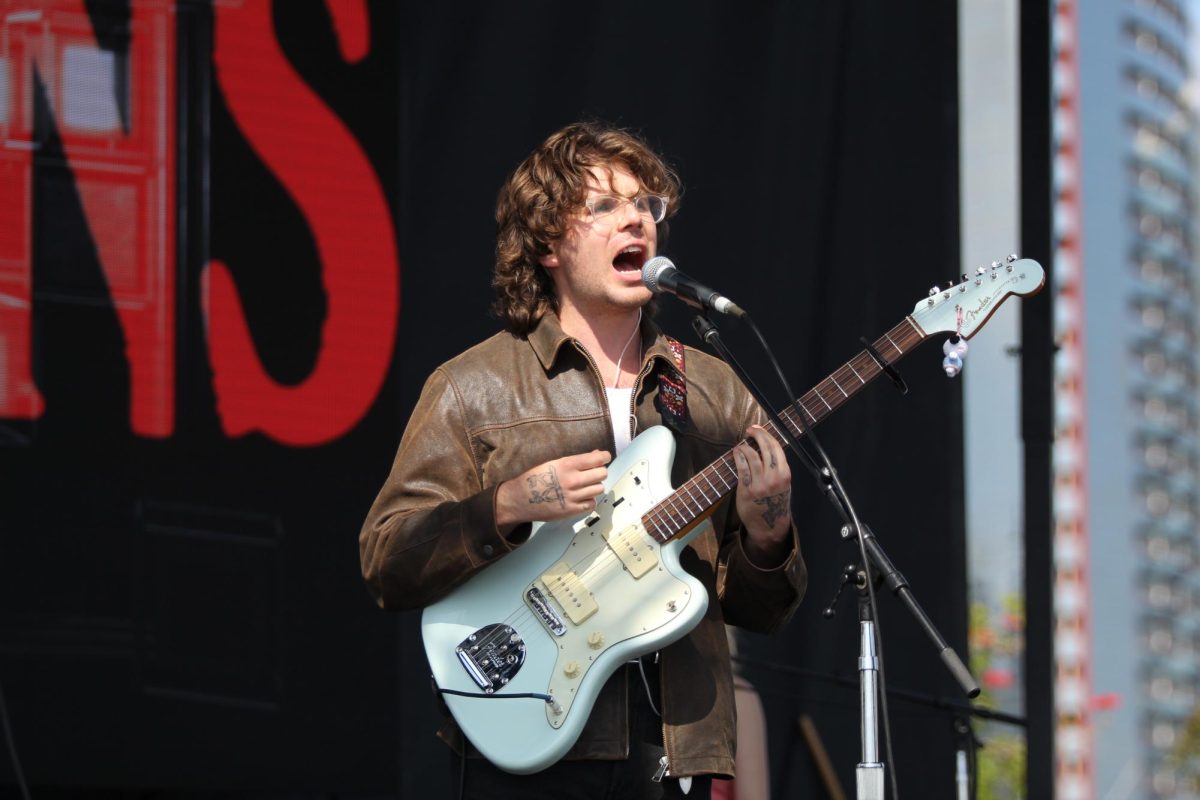

Photo courtesy of National Archive.