After a couple hours of scavenging the underground of the internet, I finally found James Foley’s execution video. It was with precaution that I watched the video, but no amount of emotional precaution could have prepared me for the sheer brutality and horrific reality of what happened to him. The unreality of the video drove home the reality of war reporting and war zones.

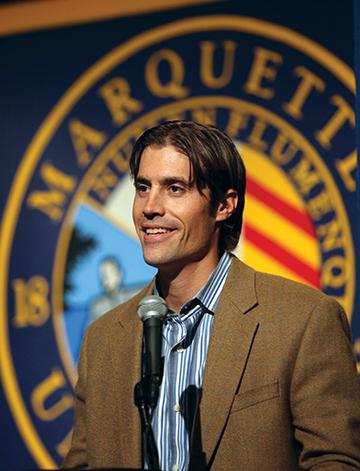

Two years ago, in 2012, former freelance journalist James Foley came to San Diego State to talk about his experiences as a foreign correspondent in the Middle East, specifically his experiences as a captive in Libya.

Just 10 months after he presented at SDSU, Foley went missing in Syria. On Aug. 19 of this year, an ISIS militant broadcasted a brutal and grotesque execution video in hopes of “sending a message to America.”

Foley’s brutal death has brought a nationwide sensational focus on him as a victim of ISIS rather than his career as a journalist. It’s time to refocus.

To many who are observers to the tragedy of this situation, Foley’s determination to report in Syria, regardless of its instability, raises questions about why journalists, such as Foley, risk their lives to crawl to the front-line and report on events which may or may not jeopardize their lives. It begs the basic question, why do journalists risk their lives at all? Why do they walk the delicate balance between life and death?

In our information age, the necessity for western journalists to report in dangerous areas is undeniably questionable as smartphones revolutionize the way people share photos and information. The events in Ferguson are a testament to the power of social media reporting. However, what makes western journalists a necessity in reporting on events abroad?

Dr. Mounah Abdel Samad, who was instrumental in bringing Foley to SDSU, said western journalists differ widely in perspective in difference to local journalists.

“For any on-ground local reporters, there is subjectivity in which they cover these type of stories,” Samad said. “Western journalists who come from another place, as Foley did, and coming with an open mind without any agenda is bring a perspective that is objective. That’s why James work was valuable.”

These questions about the necessity of western journalists in the Middle East are important ones. However, from a historical standpoint, they aren’t new.

Foley’s story is one of a larger one in which hundreds of journalists have lost their lives pursuing difficult stories in politically unstable areas.

In 2002, journalist Daniel Pearl left for Pakistan to pursue a story on infamous “shoe-bomber” Richard Reid and his relations with Al-Qaeda. Pearl left for an interview with a source, was captured and brutally decapitated. Before his death, Pearl was forced to make a VHS tape for the American government verbally denouncing and condemning American foreign policy.

Even as we go about our day here at SDSU, journalists are fighting to report on narratives that might otherwise be drowned in the tragedy of their situations. Journalists, such as Adam Nossiter of the New York Times, are in deep with the Ebola outbreak in Nigeria risking their health to report on the devastation the disease has had on social and political infrastructures. Journalists brave devastation both from Israeli and Palestinian fronts in the Gaza conflict to reveal the horrors of war.

It’s under this perspective when we see journalists less as simple reporters but soldiers of truth. Brave journalism can change a nation. Pulitzer-prize-winning war photographer, Nick Ut’s photo of 9-year-old Kim Phuc running naked down a road away from a napalm attack changed the way the nation viewed the Vietnam conflict. Powerful reporting, such as Ut’s photo, illuminate the necessity of why we need brave journalists to report these stories.

These are narratives about journalists in separate times, across different areas and issues. However, they tell a united message relevant regardless of the time, place and situation they’re in. It’s a message that has been made strong with Foley’s death, unfortunately.

Reporting difficult stories are crucial, but they come with difficult consequences.

Both journalism students and journalists need to think long and hard about the types of narratives they want to pursue and the consequences of such journeys as they begin to develop their voices in the media. Foley’s story is one of the hundreds who have died because they believed in the importance of broadcasting these issues.

The great tragedy of this situation is Foley’s stories are just now getting attention because of the consequences of his death, which isn’t how it should be. Much of the attention in the Middle East and other politically unstable areas are stories about the consequences of devastation, both positive and negative aspects. We should be taking an extra step to educate ourselves and empathize with the stories journalists are risking their lives to carry out.

These aren’t just stories, they’re a stepping stone to a call for action.

“A starting point is bringing something to your awareness and once it’s brought to your attention you can start from there.” Dr. Abdel Mounad Absad said in regard to the importance of journalistic bravery. “That’s what’s important for journalists. They bring voices to the voiceless. The key here for what James was doing was that he was looking at people who don’t have a voice and giving them a voice in international media. That, I think, is a tremendously powerful act of bravery.”

We don’t find our stories or passions by remaining idle. We find stories the way miners find diamonds. We start by taking the first step, by digging.