In philosophy, progressivism is centered on the advancements in economics, sciences and social organization and their role in improving humankind. Progressive ideology was undoubtedly influential on the foundation of the Progressive Party in America in 1912. It manifested as a response to Theodore Roosevelt’s predecessor, William Taft, who leaned too conservatively for Roosevelt’s liking. With the dissatisfaction of Roosevelt and a few other Republican Party reformers, the Progressive Party began to establish an opposition to the two-party system.

The party’s platform encompassed some of the most reformist ideas that would become part of the political landscape. It included strict limits and disclosure requirements on political campaign contributions, registration of lobbyists, a national health service to cover all existing government medical agencies and social insurance to provide for the elderly, the unemployed and the disabled. It also called for limiting the ability of judges to order injunctions to limit labor strikes, a minimum wage law for women, an eight-hour workday and women’s suffrage.

Although Roosevelt lost the election, the Progressive Party made history by being the first third-party to get more electoral and popular votes than one of the two major parties. Something essential that was lacking in the 1912 Progressive Party platform were the voices and support of the black communities, particularly in the South. Roosevelt intentionally excluded black communities because he felt they were corrupt and ineffective. Although this is an unfortunate truth, it is one to remember. It serves as a reminder of what necessary changes can be made to improve a political party.

This realization was present and incorporated in the platform of the re-established Progressive Party in the late 1940s. The Progressive Party, this time, reemerged in 1946 with Henry Wallace as its leader. Wallace served under Franklin Roosevelt’s administration and rose to prominence because of his critiques of Harry Truman’s Cold War policies. The platform of this Progressive Party included desegregation, establishing a national health insurance system, expanding welfare and nationalizing the energy industry.

This era of progressives also championed civil rights not only by standing with the Native American, black and Jewish communities, but by advocating for social programs like better health, housing and educational facilities. The policy proposals were a staunch difference to what Truman and his supporters were running on. Truman’s campaign veered away from directly supporting black communities. The strategy was rooted in fear of losing support from Southern Democrats, also known as the Dixiecrats. In essence, it did cost Truman support, but it also revealed the Democratic Party’s limitations for progressive causes in fear of losing the support of white voters. It is a similar issue in today’s conversations of electability.

The policies of the early and mid-1900s might sound familiar today. The 2020 Democratic candidates are advocating for Medicare-for-all, livable wages, free college education, environmentalism, immigration reform, social justice — the list goes on. Each candidate seems to be trying to prove they’re more progressive than the other which is typical in the history of elections. Some candidates have the record to confirm it, while others would like to believe they do despite their past and current deeds. The rejection of progressive ideology as a strategic impulse in order to maintain the interest of moderate voters also hasn’t changed.

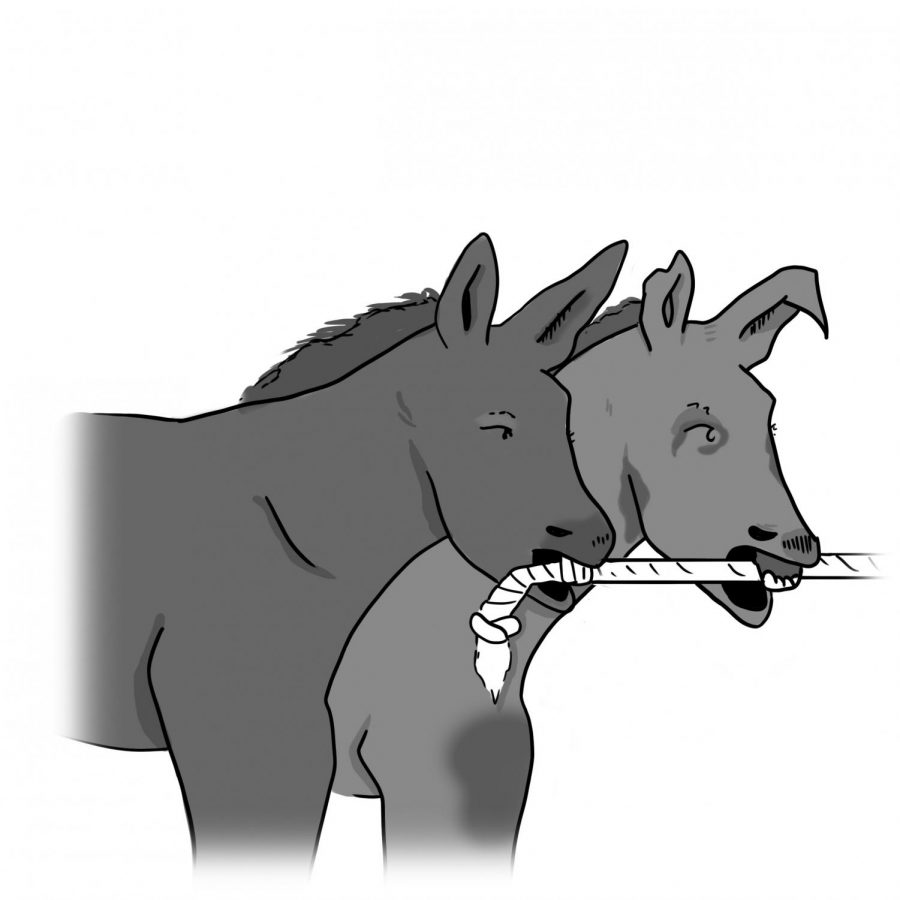

Despite this race, it is evident that even though some candidates push for progressive causes, others remain adherent to the present and past. The divide developing in the Democratic Party is nothing new. History shows there has always been a trope-like struggle between new progressive voices and the veteran voices who focus on preserving their power. The present conflict is not whether new ideas should influence the existing party. Instead, it centers on whether the prevailing party still serves those who granted them power. If the answer is no, then the result is to search for someone who will, which can pave the way for populism.

This dynamic between progress and maintenance, however, reaches beyond America. Countries like Argentina, Brazil, Britain, Italy, France, Germany and Poland are struggling with the backlash against an establishment or elite class seen as a failure in serving its people. Different sides of the political spectrum may have various reasons for feeling abandoned or unheard, but what they can agree upon is the experience of feeling dismissed. This abandonment derives from anxieties of helplessness, and when a party can’t produce a vision to relieve those anxieties, they will become the perpetrators of failure.

In the Netflix documentary “The Edge of Democracy,” Petra Costa interviews Gilberto Carvalho, a former general of the presidency for the Workers’ Party. While being interviewed, he acknowledges the failure of their party to remember why they were in power. As a consequence, support brewed against the party, ultimately paving the path to elect Jair Bolsanaro. Carvalho referred to what the Workers’ Party forgot as the “one foot in/one foot out strategy.”

He explains, “the foot on the outside keeps us connected to the social struggles knowing that in capitalism, you only get your rights by mobilizing and fighting. The inside foot is being inside of the institution, seeking to change it.”

This combination seemed ideal, but as the party grew, Carvalho remorsefully admits that the outside foot, comprised of voters and constituents, was no longer acknowledged. The Workers’ Party began to rely more on congress, and they even became friends with the “big fish.” The organization shifted into naturally seeking campaign financing instead of making the political reform needed to remove business interests from campaigns. He describes the clientelistic relationship installed by companies and candidates as the root and “mother of all corruption.” After feeling betrayed by the party, the people of Brazil began to shift their support away from the Workers’ Party, leading to its political demise.

It serves as a reminder that comfort and the apprehension of losing control is not a basis for lingering in power. The consistent effort to move forward is the mandate of progress. These lessons, although acquired abroad, apply to the politics of the world, and America is no exception.

Both political parties in America are dealing with the fallout of displeasure. Conservatism within the Republican Party is eroding into nationalism while the Democratic Party is again struggling with its platform and policies that prove their commitments. The Democratic Party is also struggling because it tries to distinguish itself as the moral party. This characteristic puts them in a situation that leaves them vulnerable to criticism for not fulfilling that standard. Declaring that they are pro-immigration and then having a previous Democratic administration, with House and Senate majorities, increase deportations in an unprecedented manner is not an improvement.

Flaunting that the party is growing with diverse and new voices but then belittling them when they speak up is not an improvement. Voting for increased military spending and intervention is not an improvement. It’s the same ideas with a different title. Without the progressive candidates, the Democratic Party’s platform would not have an outline to tackle the issues of today’s voters. They would only be maintaining the status quo. The Democratic Party can’t seem to find what it stands for, and it is evident in their overcrowded primary debates.

What will become of the Democratic Party is the choice not only of the voters, but of the officials who guide the party. Since 2016, the Democratic Party failed to design a platform that is appealing to what used to be their base and new voters. They instead reverted to their age-old tactics of displaying themselves as the best alternative to the other party. Unfortunately, merely saying one thing for appeal is not going to be enough.

The Democratic Party focused on the Muller report more than it did on developing a platform. When the results were inefficient, it left them with three years gone and no platform or other strategies to show for it. The progressive wave was made not by the veteran Democrats but by new effectiveness that won the House of Representatives in 2018. The effort needs to come from within and with consistency and results that people can relate to, which progressives have proved works. The opportunity for progressive candidates passed the Democrats in 2016, but will have a chance to come to the forefront in the 2020 election. Now it is only a question of whether Democrats will learn and prosper or fall back into a cyclical history.

Charlie Vargas is a senior studying journalism. Follow him on Twitter @CharlieVargas19.