No matter what country you are in, there is a plethora of economic issues that can be debated.

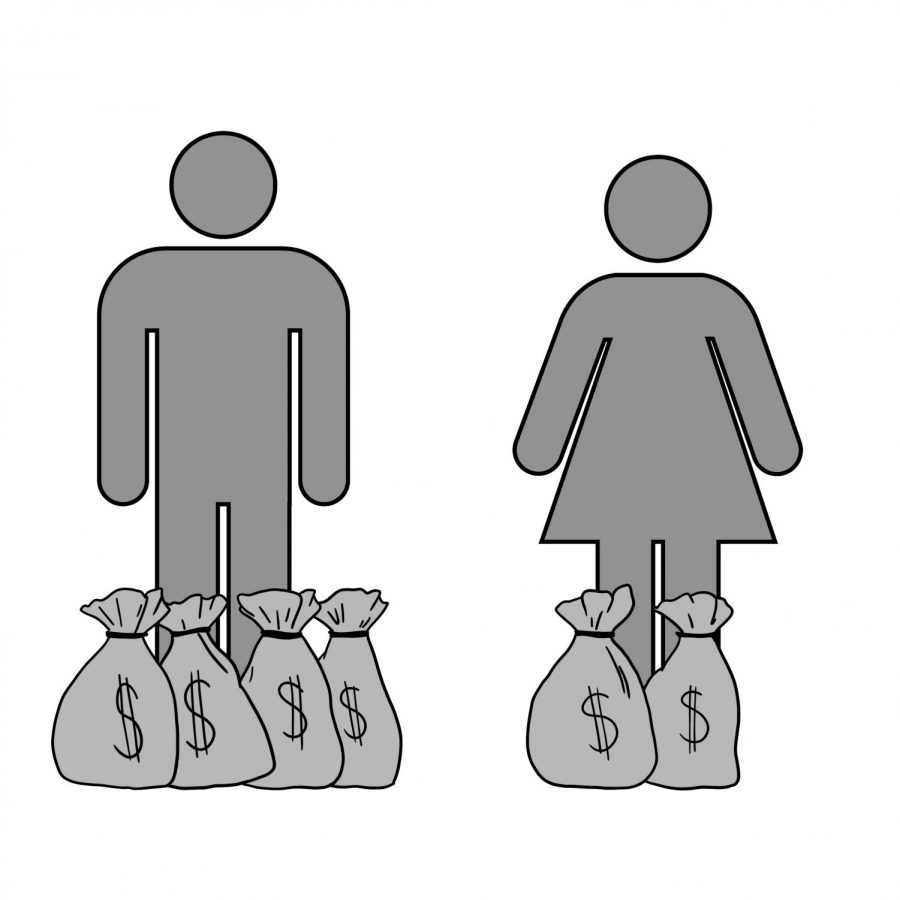

Not all these issues are necessarily relevant to most people, but the gender pay gap is something worth observing.

Data taken from the U.S. Census Bureau in 2018 shows us that Hispanic women on average reported earning only 54.5% of the income that White men reported, but that same number was 83.8% of the income earned by Hispanic men. Asian women earned 90.2% of the income that White men reported, but that number was only 79% of the income that Asian men earned. This tells us that not only is income correlated with gender, but race as well.

The gender pay gap affects both men and women around the world, including many here in San Diego. One of the groups to be most affected by the gender pay gap is Hispanic females, according to multiple studies, including one performed by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. The institute is showcasing major scientific work done by professionals across the nation to describe and provoke public change to alleviate the gender pay gap.

Statistical data has shown us that some of the disparity between the wages earned by men and women can be attributed to the choice of many women to pursue motherhood. There are physical limitations of new mothers regarding their children. Children need time, supervision, love and a million more things.

The responsibility of childrearing can be traced back to the hunter-gatherer era. Many women would take their children to gather so the hunters wouldn’t have to worry about keeping their child quiet while stalking animals. This allowed them to watch their children in the field and provide utility to the group.

This lifestyle choice of having children has affected career aspirations of women who want to be a mother over the years and continues to affect women today. This, however, is not the entire story.

Women who are pursuing degrees in science, technology, engineering or mathematics face not only academic challenges, but cultural and lifestyle challenges as well.

Shelley Correll is a published scientist at Harvard who has studied the issue in depth, written multiple articles and conducted experiments focused on the gender pay gap. She argues the largest factors affecting the wage gap are career preferences and motherhood. These are unsurprising conclusions to some, but Correll took it a step farther to examine how career preferences can change in university students.

Correll’s experiment published from the American Sociological Review in February 2004 included 94 gender randomized, first-year undergraduate students. She wanted to test the existing theory that women were underrepresented in STEM fields due to stereotypes of male competence both in specific tasks and in general.

This experiment gave students a series of arbitrary tasks they were told measured a nonexistent skill or ability. The test was designed to fail and the scores that the students were given meant nothing. Before beginning one task, the students were told men generally performed that kind of task better than women. Before other tasks the students were told men and women performed equally. The students were then given criticism over their work and were asked to review their own performance and overall aptitude.

The experiment found women rated their own performance more negatively than men. These students all failed the same tasks, but the women were harsher with themselves than the men were. The experiment also found that the women rated their own aptitude lower after completing the tests, while men reported their aptitude higher. Women saw their own ability diminished even though the test and results were identical to the men.

Correll continued to ask the students if they had any interest in a field of work that would require this fake skill, and women reported less interest than men in pursuing a career in a potentially profitable field related to the false ability.

These findings can be applied to women pursuing degrees in STEM fields. STEM workers tend to earn more on average than their non-stem counterparts. STEM is also one of the most male-dominated areas of study. In my opinion, women are capable of attaining high-paying jobs in STEM fields, and it would be a shame for a prospective woman in the STEM field to be discouraged from pursuing a career in STEM due to narrow-minded stereotypes.

Just because a stereotype exists, it doesn’t mean it holds true in every case. Failing at one test or one task doesn’t necessarily predict later performance. Women pursuing degrees in STEM fields are facing large cultural barriers in the form of stereotypes and career aspirations could be thwarted by insecurity over level of performance or aptitude, when in reality this may not be the case.

Social change rarely comes from inaction. If we, as a society, want to see a change in the wage gap, it will require action on the individual level. Women pursuing high-paying STEM jobs are creating change that they want to see in the world and the positivity is contagious.

Everyone will fail and receive criticism, these are barriers that we must overcome in life if we ever want to see success. I have failed more times than I can count, and I know that sometimes the best way to do something right is to first mess it up in every way imaginable.

By pursuing a STEM degree a student can not only work to end the wage gap by attaining a high salary, but also can help to change public image and kill the silly stereotype that male competence is greater than female competence.

Ryan Janics is a senior studying economics.