What makes an elementary school unique?

The teachers? The classrooms? The location?

For the Campus Laboratory School, all of these elements made it different than the average elementary school.

San Diego State was founded in 1897 as a training facility for teachers, then called San Diego Normal School.

In 1900, another school was created on the campus, the Campus Laboratory School. The CLS was created to provide schooling for elementary, middle and high school students.

The CLS gave teachers in training hands-on classroom experience. In 1910, the high school was discontinued due to an increase in enrollment which caused space issues. The elementary and nursery school were moved into a different building.

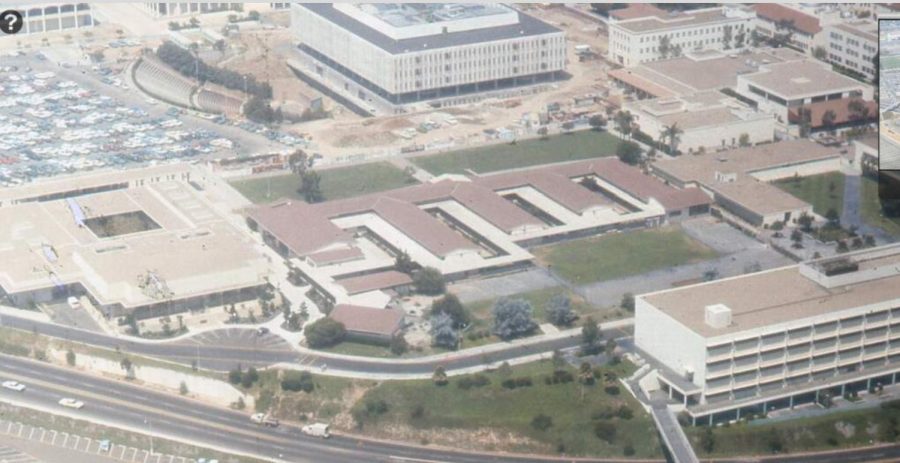

In 1953, the college campus was expanding and a new building was built to accommodate the CLS. The building was located where Student Services West stands now. However, the CLS building was demolished in 1991.

George Sorensen, who attended the CLS from kindergarten to sixth grade, described the environment. He said a master teacher would teach and then student teachers would come in and interact with the children.

Occasionally, a class of students would sit in the back of the room on folding chairs and observe the children.

“It made you feel more comfortable with adults because you were always around them. Sometimes there would be 20 people watching,” Sorensen said.

Echoing this, Phil Frye said there was a year where there were 20 student teachers in the fall and 20 in the spring.

Keith Christensen, who attended the CLS from nursery school to sixth grade, said it was normal to be watched.

“It was a teacher school, teaching teachers how to teach,” Christensen said. “I think it was a benefit to education and also gave us an education too.”

According to SDSU’s Special Collections & University Archives, the CLS experimented with individualized curriculum, a non-graded organizational structure, team teaching, bilingual programs, programs for special needs and gifted students and more.

Dr. James Reston, the final principal of the CLS, said the main purpose of the school was experimentation.

When learning about the pioneers, Sorensen, Christensen and Frye recall building a log cabin in the patio outside their classroom to help with the comprehension of the subject.

“It was part of the learning process,” Frye said, “how they made it, what they wore. It was really in depth.”

Some of the lessons at CLS were recorded for college students who were studying to become teachers. They could observe student-teacher interactions with these tapes if they weren’t able to observe in person.

The other purposes of recording students was to assess the cost, identify which lessons students should observe and to help the field better understand technology for teaching purposes. Frye remembers being taken to the broadcast room and being recorded.

Sorensen and Christensen both recall having guest speakers come into their class and speak. Sam Hinton, a 1950s folk singer and a teacher at University of California, San Diego, came to their class annually to entertain them.

Another guest who came multiple times was Theodor Seuss Geisel, otherwise known as Dr. Suess. Sorensen has a signed book by Dr. Suess from one of the visits.

Faculty from various departments at the college would come into their class and help teach. Mr. Gates, an art teacher, would come in and teach the children how to paint and a music teacher would teach them how to play different instruments.

Even though the school was discontinued, it was highly sought after by parents. The school was a first come, first served basis. Parents put their students on the waitlist soon after they were born to try and ensure them a spot by the time they were ready for school.

When the school closed, there were 2,400 applications on the waitlist.

Sorensen and Christensen were both put on the waitlist when they were born. Two weeks after he was born, Frye’s mother put him on the waitlist to attend the CLS. Frye’s two older brothers also attend the CLS.

In 1970, The Daily Aztec did an article on the upcoming changes to the CLS. One of the things that was planned for the upcoming semester was a bilingual program and the continuation of multi-age classes.

However, in the summer of 1970, California cut funding for the CLS with the intent to save $1.1 million, not adjusted for modern inflation. The state wanted all five experimental schools to be transferred to their respective local public schools.

Other similar schools were being closed in San Francisco, Humboldt, Fresno and Chico. Between the five cities, a total of 1,212 students were placed in public schools during the fall of 1970.

This upcoming April, the CLS graduates of 1963 will be holding a reunion lunch with almost 80% of graduates attending. Sorensen, Christensen and Frye will be in attendance.

“When you see them, it’s like you saw them yesterday because you share so many memories,” Sorensen said. “In CLS, you pretty much knew everyone from when they were 2 feet tall and four years old.”

This is only the second time the Class of 1963 will be having an official reunion. The first time graduates from the school reunited was in 1991 when the CLS’s final building was being demolished.

Last August, Will C. Crawford High School had a 50th reunion where some of the CLS graduates attended. Based on that mini reunion, it was even more of a driving force to get the whole class together.

The CLS Class of 1963, currently have an email chain where they are reminiscing on things they remember from CLS.

“Surprises and delights me that we would make an effort all these years later, it really shows the experience we shared,” Frye said. “It was a fabulous experience and I wouldn’t change it for the world.”