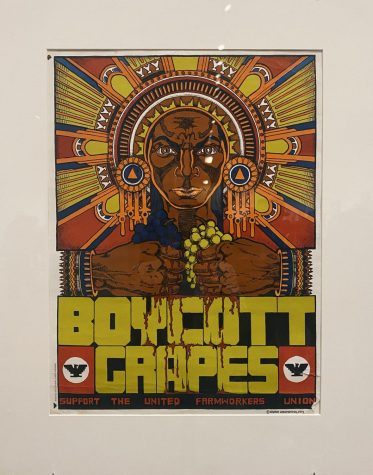

Amidst a myriad of colorful images depicting everything from an Aztec clenching a cluster of grapes to a print that reads “Viva La Raza,” was a diverse compilation of people absorbing the art around them.

They were at the opening reception of a new SDSU Downtown Gallery exhibition where they celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies on Thursday, Feb. 20.

The exhibit, “Chicano/a/x Printmaking: Making Prints and Making History – 50 Years of Art Activism,” is dedicated to showcasing the work of Chicano artists who have turned to the art of printmaking to communicate social and political issues.

Borrowing from a collection of more than 10,000 works of Latino art owned by Gilberto Cárdenas and Dolores García, Chicana and Chicano studies professor Norma Iglesias took on the lead curator role and organized the exhibition into six chronological sections.

Free and open to the public, the collection will remain on display at the donation-based gallery until April 5.

According to Iglesias, the collection spans from the ‘60s until today. She also mentioned each section is dedicated to the different eras and themes of the Chicano/a/x movement — political expression, culture and tradition, to name a few.

This layout is intended to help the viewer observe and navigate through the evolution of the ideas and activism of the Mexican-American communities in the country. And while the relationship between printmaking and the Chicano Movement ties back to Mexican art, Iglesias said this continuous wave of activism transcends ethnicity.

“Maybe people from Guatemala feel part of this community and have the same challenges and same struggles so they identify with the Chicano cause,” Iglesias said. “You could be part of a movement that is not exclusive of Mexican-Americans because you feel part of it.”

Indeed, once the doors to the gallery opened, a stream of different people from different backgrounds started to pour in. They were scattered around the gallery, pondering the different pieces that filled the white space.

According to the SDSU Downtown Gallery Director Chantel Paul, the gallery received more than 320 guests throughout the event, marking the second highest attendance to date.

This diverse group of people took to the heart of the gallery to hear some opening remarks by those involved with the curation of the exhibit.

Moments after, a gallery tour led by scholar Amelia Malagamba and Gilberto Cárdenas began.

The first stop on the tour was a section titled “Organizing Revolts – Organizando Revoltas.”

Viva La Raza (1998) by the Mexican-American artist Salvador Roberto Torres is one of the many prints in this section. This part of the exhibit not only marks the beginning of the collection but symbolizes the birth of the Chicano/a/x movement as well.

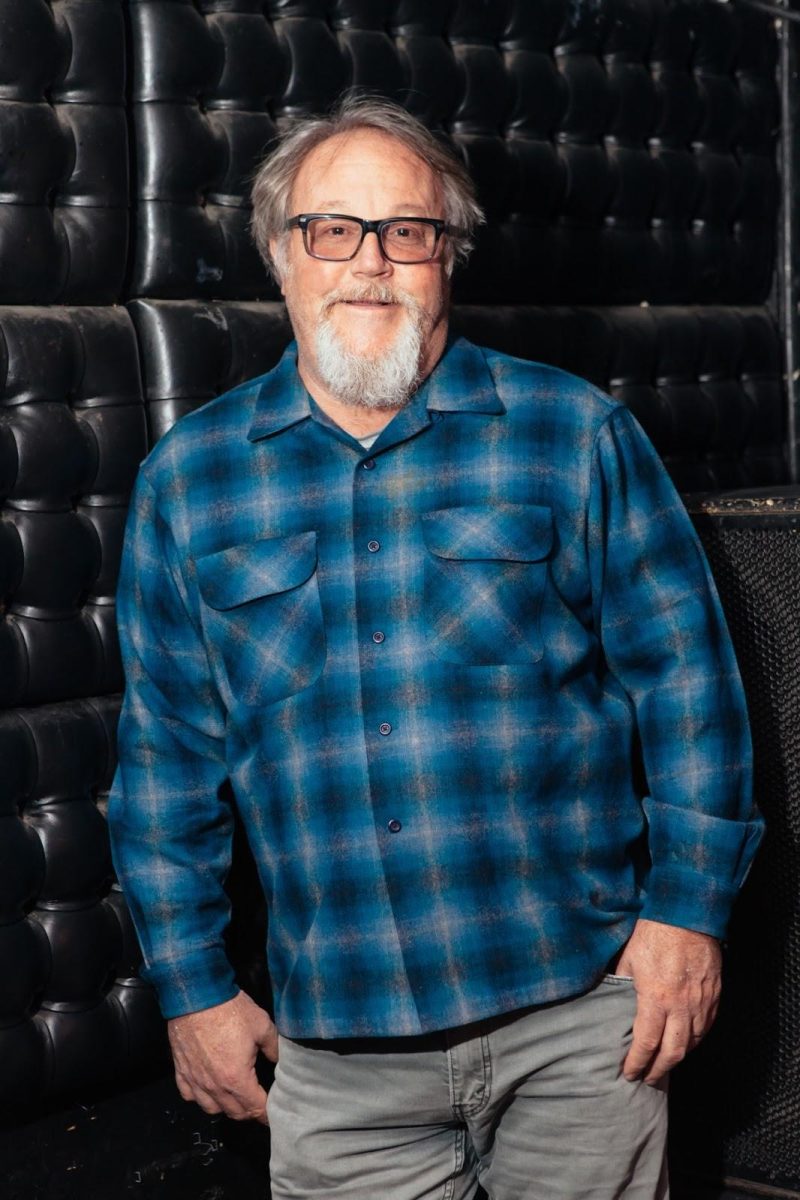

Wearing a fisherman’s vest and a brown beret, Torres shared a few words about his involvement with activist groups in the ‘60s.

“We (The Brown Berets of San Diego) made a partnership with the Black Panther Party and our collaborations were the same,” Torres said. “The healthcare of our community, the preservation of our women and children and our seniors through both observing and serving.”

Next was a section called “Everyday Life – Vida Cotidiana.” Here lives a colorful assortment of images depicting the lifestyles and cultural traditions of the Chicano/a/x communities.

Interdisciplinary studies senior Macarena Bayolo was particularly moved by the variation of prints and colors.

“I think it’s really beautiful,” Bayolo said. “I like seeing how different they all are but they all have a similar message and even though they’re all different styles, it’s very emotional work.”

Other topics portrayed in the exhibition include mass migration, family separation, extreme poverty, racism, hate and climate change.

Although the Chicano/a/x purpose and mission remains in action and continues to evolve everyday, the exhibition concludes with a section called “Borderland Ways – Formas fronterizas.”

This area has a focus on the geopolitical border between Mexico and the U.S.

One of the Chicano artists in this section is Victor Ochoa, who was one of the first silk screen printers in San Diego during the ‘60s. For him and his fellow Chicanos, posters were a way of communicating their mission during a time when their cause lacked media coverage.

“The media coverage for us was zero,” Ochoa said. “I used to handwrite and hand draw those visuals that were very much our way of getting the information of the issues to the community and that was our main effort: to educate.”