Before the likes of Megan thee Stallion and Cardi B took to the mainstream with displays of confident sensuality, Betty Davis, aka “the queen of funk,” made adoring men faint, radio disc jockeys feverish and Bible-thumping mothers gasp at her enthralling sex appeal.

Like many Black artists who pushed the boundaries of musical possibilities in the ‘60s and ’70s, Davis never received the acclaim and adoration she deserved. Plain and simple. Racism and misogyny played a significant part, with her voice being silenced by those who never attempted to understand her.

Born Betty Mabry, Davis’ musical journey began at the age of 16 when she moved to New York with ambitions of a modeling career. She soon became an important figure in the ‘60s Greenwich Village counterculture scene and began recording music under her birth name while appearing in “Seventeen,” “Ebony” and “Glamour” photospreads.

While living in New York, Davis became acquainted with several rising artists, including the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone, and began making her name as a songwriter, penning songs like the Chambers Brothers’ “Uptown (To Harlem),” an underrated classic that finally received proper due in Questlove’s “Summer of Soul” documentary. She was a perfectly symbolic character of this artistic “changing of the times” period.

But everything changed in 1968 when Davis (then still going by Betty Mabry) entered a relationship with jazz pioneer Miles Davis. Over the course of their brief and chaotic one-year marriage, Davis introduced him to modern fashion as well as the psychedelic pioneers Hendrix and Stone, sparking Miles Davis’ jazz fusion epiphany as he started incorporating electric guitars and synthesizers into his repertoire.

Davis also served as his creative and aesthetic muse, appearing on the cover for his 1968 album “Filles de Kilimanjaro” and inspiring the title of Miles Davis’ most seminal album “Bitches Brew.” Davis’ inspiration on her husband was monumental and shifted the entire landscape of the jazz genre. However, the musical triumphs of their marriage were undermined by Miles Davis’s volatile nature, highlighted by constant jealousy, paranoia and abuse, which ended things quickly.

Up to this point, all the loose singles and unreleased tracks Davis had recorded over the years were either tossed aside or shoved in a vault, only seeing the light of day in the 21st century. Davis then moved to London for modeling work, before finding a home in San Francisco after writing songs and planning musical projects abroad.

Davis intended on recording a project with San Francisco rock band Santana but after her plans stalled, she recorded her debut solo album with her backing band Funkhouse. Her self-titled debut “Betty Davis” was released in 1973 and provided to be a daring introduction to her erotic raunchiness, as well as the deep, howling voice she used to sing.

However, things really came together on her second album “They Say I’m Different” which can be described as a wild, funk-filled odyssey that’s raw, exciting and truly “different.” Songs like “He Was a Big Freak” and “Don’t Call Her No Tramp” were provocatively funky and showed women could be just as nasty as men when it came to music.

Between the release of “Betty Davis” and “They Say I’m Different,” Davis began gaining a reputation as an explosive live act.

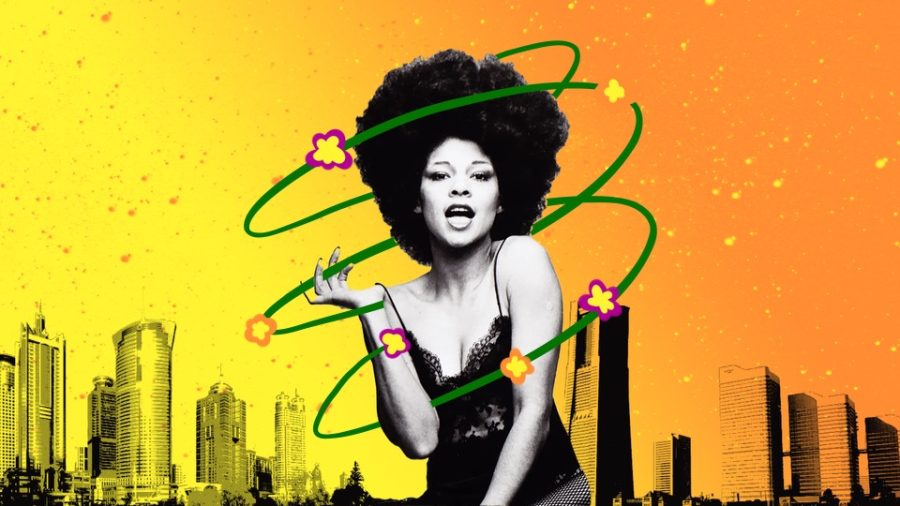

When she graced the stage, Davis brandished a luscious afro, often paired with fishnet stockings, knee-high boots, and shiny bikini tops. She screeched and yelped into the microphone while gyrating and leaving a lingering inflection on the nastiest parts of her lyrics. (Before Jill Scott was simulating fellatio on a mic, Davis was using hers as a prop penis.) Davis was a palette of unhinged sex appeal, something many audiences weren’t ready for or just didn’t appreciate for its vulgarity.

The height of Davis’ short-lived career was her third studio album and first project on a major label was “Nasty Gal,” released in 1975 on Island Records. Her badness and boldness peaked here, especially on the title track.

However, any artist who toed the line between self-expression and obscenity risked censorship, and this was especially true for Davis.

During the ‘70s with the emergence of second-wave feminism and the ERA (Equal Rights Amendment) movement, actresses such as Pam Grier were under fire for portraying overtly sexual Black characters like “Foxy Brown” and Davis was lumped right in with this supposedly unruly image of Black women. Moments like this showed that the era of free love, empowerment and embracing femininity at its most divine and vulnerable only applied to white women. Any Black woman who opposed the norm was ostracized and criticized for being a negative portrayal of the entire gender.

In opposition of Davis, the NAACP partnered with conservative religious organizations to boycott her shows and prevent her songs from receiving radio play. There was no objection to any male rock stars who stripped their shirts off and went wild to get the attention of the ladies, but Davis presented an issue. She was an overly confident woman who championed her sexuality, and for that, she had to be stopped.

Despite her obvious skill, Davis’ career never translated to landmark success. Not even modest success. With little to no radio play, and even with support from icons of the ‘70s like Richard Pryor and Carlos Santana who understood the talent they were experiencing, her career came to a sudden conclusion in 1976. Davis was dropped by her label and quietly retired, or vanished as those who know her say.

Davis’ life after music was seen as mythical with her retreat from the public sphere adding to her larger-than-life cult figure presence. She showed up for a brief spell in Tokyo in the mid-80s while playing with a new band but this was only temporary, and Davis rejected an idea of any large-scale comeback.

Davis wasn’t going to let anyone prevent her from doing things the way she desired and she refused to compromise her vision. Yet, this rejection from the industry had its consequences.

Before passing on Feb. 9, 2022, Davis lived a life of solitude, even declining to appear on-camera in the documentary about her life (“Betty–They Say I’m Different”). When she passed, several articles and tributes were written honoring her legacy, but Davis had been so broken down by the time of her passing that even when acceptance came it was too little, too late.

Be sure to appreciate the truthfulness of today’s “nasty gals” before they cease to exist.