Stress — the all-encompassing word that describes daily life as a young adult.

Thank endocrinologist Hans Selye for the term’s modern meaning related to emotional and mental strain. Until about 50 years ago, “stress” was used mainly to describe physical pressure on an object, but Selye managed to renovate the term with a psychological connotation — just in time for millennials to coin it as their credo.

Many San Diego State students feel the weight of the word daily, and with finals looming, the side effects of stress seem amplified.

“It’s challenging to simultaneously get good marks in school, maintain relationships, participate in extracurriculars and seek outside work experience,” senior marketing major Hunter Podell said.

In SDSU’s 2010 Healthy Minds Survey, 37 percent of students believed they needed help for mental and emotional problems and 18 percent reported 3-5 days of academic impairment from poor mental health. SDSU has not conducted a mental health survey since 2010, but is planning on participating in the upcoming National College Health Assessment in February 2016.

“Going to school and working full-time creates a daily burden of stress,” English junior Kristen Henry said. “I know so many people in the same situation who need to work to support their education. Evening classes are limited. The school pushes for students to take full course loads and to graduate in four years. It’s a lot.”

The 2010 assessment deemed schoolwork the most significant source of stress for students, followed by financial concerns. It also found 17 percent of SDSU students were struggling with depression or anxiety — a phenomenon only expected to increase in correlation to recent national statistics.

“Anxiety is replacing depression as the top issue,” Counseling and Psychological Services Director Jennifer Rikard said. “It’s the national trend and the trend at SDSU. After anxiety and depression, people most often come in for relationship counseling, school-related stress and financial concerns.”

The idea that anxiety is tipping the scale of work-life balance on campus is not unique to SDSU. On a national level, millennials are struggling with mental health at staggering rates.

More than 85 percent of college students felt overwhelmed by all they had to do at least once within the past year, according to the American College Health Association. More than half of survey participants felt that way within two weeks of taking ACHA’s 2015 National College Health Assessment — the same assessment SDSU will use next semester.

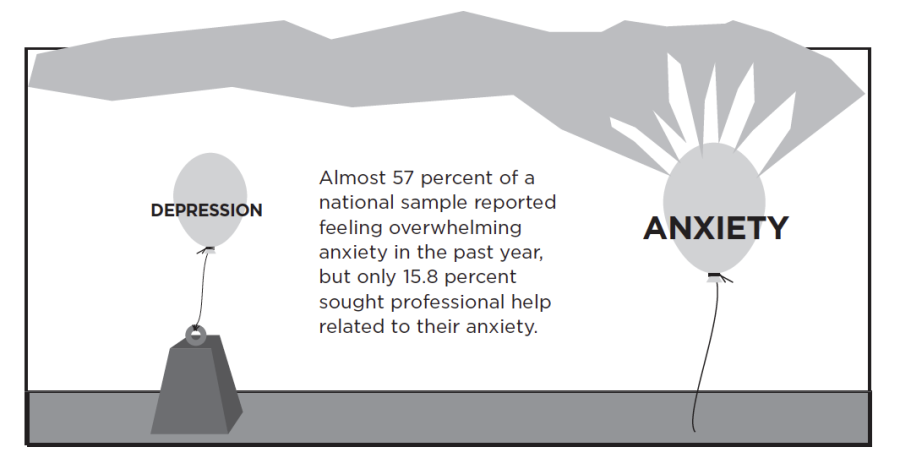

Almost 57 percent of this national sample reported feeling overwhelming anxiety in the past year, but only 15.8 percent sought professional help related to their anxiety. When presented with a list of 12 common aspects of life, survey respondents chose academics most often as the primary source of stress and 45.1 percent of respondents reported schoolwork to be “traumatic or very difficult to handle” within the past year.

The increasing levels of poor mental health have been a popular topic among psychologists in recent years.

The cause of this overarching generational mood swing is rooted in early childhood development. Essentially, baby-boomer parents raised now college-aged children to have high expectations for themselves and, moreover, raised kids to believe they could reach any goal, no matter the feat. Millennials grew up hearing, “You can do anything if you work hard.”

Now, young adults face a significant discrepancy between expectations and reality in college and in the workplace.

In his article “Why Generation Y Yuppies are Unhappy,” blogger Tim Urban simplifies the story with this formula:

Happiness = Reality – Expectations.

It’s dangerous to assume an individual’s “grass will be greener” than their peers simply as a result of working hard, Urban writes.

“‘Generation Me’ (young people born between 1970-2000) has been taught to expect more out of life at the very time when good jobs and nice houses are increasingly difficult to obtain,” SDSU psychology professor Jean Twenge wrote in her recent book, “Generation Me.” “All too often, the result is crippling anxiety and crushing depression.”

Twenge’s research also indicates the time period when people are born is four times more likely to affect anxiety levels than family environment. It seems millennials have a predisposition to be more stressed, anxious and depressed than their parents and grandparents.

Fortunately, there’s a silver lining. In addition to the classic remedy of exercise and proper nutrition, there are several habits, as well as resources available on campus, young adults can utilize to improve their outlook on life.

One practice in Urban’s toolbox is to stay wildly ambitious and resilient.

Another is to unplug.

Millennials use social media, where everyone is distorting their lives to seem perfect, as a benchmark for reality, thus fueling unrealistic standards.

If perception practices aren’t enough, there are resources available for SDSU students at Psychological Services, located at the Calpulli Center in room 4401.

The center offers private and group counseling for stress, anxiety, depression and overall well-being, including grief counseling specific to young adults. One of the paramount workshops, COPE, is a customized program specifically tailored to students with hindering stress.

“My stress has probably quadrupled after the transition from pre-major to major,” a senior nursing student who wished to remain anonymous said. “Psychological Services is helping me to be proactive in trying to handle my anxiety in a healthy way.”

Psychological Services also acts as a hub for wellness, welcoming students to drop in and enjoy hands-on relaxation activities and a comfortable place to study. One fan favorite feature is the Alpha Chambers, the egg-shaped relaxation pods designed to increase alpha waves in the brain and reduce stress.

Additionally, during finals week, keep an eye out for the “relaxation station” for free Scantrons, water, food, advice and quality time with beloved therapy dogs.

Students can start services with a phone consultation (619-594-5220), where a therapist will help determine the best-suited program. If someone is experiencing a mental health emergency, call the Counseling Access and Crisis Line. The 24-hour service can be reached at 1-800-479-3339.