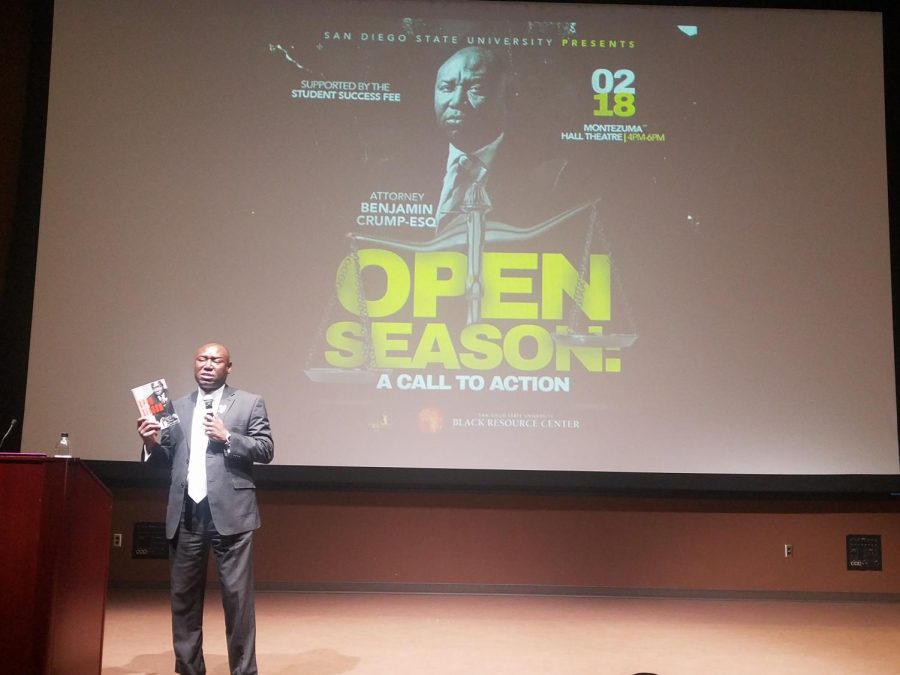

On Feb. 18, the Black Resource Center invited renowned attorney and author Benjamin Crump to speak at Montezuma Hall Theatre about his achievements and work.

Crump’s history as an attorney includes high-profile cases involving civil rights. He represented the families of Alesia Thomas, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Tamir Rice.

Crump also spoke of his book, “Open Season: Legalized Genocide of Colored People.”

“The title of the book was intentional, and I am unapologetic because it makes a point,” Crump said.

Crump explained that he decided on the name of the book after the events in the killing of Michael Brown. He said he was inspired by the way the case was handled by law enforcement and the court, such as the dismissal of the 14 witnesses who saw Brown put his hands up before being killed.

This and other events around the case led him to think about the ways that the justice system is complicit into an issue he equates to genocide.

“It is more important how they kill us every day, in every city, in every state (and) every courtroom in America,” Crump said.

Crump also said the book serves as a continuation of the actions of black leaders Paul Robeson and W. E. B. Debois, who submitted a petition to the United Nations in 1951 asking for recognition of black genocide in America. Their petition based its argument on lynchings, legal discrimination, police brutality, inequality of health and life conditions prevalent in black communities. Crump’s book extends the conversation of genocide to modern times.

The concept of what Crump refers to as “legalized genocide” involves a subtle form of causes of death, different from cases that involve police brutality and excessive force. One of these methods Crump said is through environmental racism.

As an example, he compared the air quality of Santa Monica and South Los Angeles to indicate how affluent communities have access to cleaner air while underserved communities of color live in pollution.

Crump also talked about the consequences imprinted on the lives of convicted felons when released from prison.

“You can’t vote, serve in the military or serve in a jury,” Crump said. “That’s just the tip of the iceberg.”

Crump explained how the consequences of being caught in a legal system that continues to punish individuals after serving their time in prison is confining. He said being a convicted felon restricts various financial aid programs and consideration for employment, while the expectation of paying for probationary and drug testing fees persist.

“It’s almost like you’re caught in a trap,” he said.

Crump said his aspiration to become a lawyer started in the fourth grade. He was influenced by Thurgood Marshall, the lawyer who led the victory of Brown V. Board of Education. Crump gave an anecdote about how he and his friends could not afford to buy lunch and instead relied on the free lunch program. The realization of unequal opportunities motivated him to fight for his community’s future, and he hopes to continue passing on his knowledge and motivation.

Some of that influence was present in the crowd. At least four students in the audience who asked Crump questions in the open forum were applying to law school.

Fourth year interdisciplinary studies major Isaiah Hardy received his first acceptance letter for law school within the last week. He said he was inspired by Crump’s discussion of civil rights.

“It was great to see another black man like myself,” Hardy said.