For centuries, science and medicine have been used as weapons against Black people, serving to both justify and perpetuate institutionalized racism.

Researchers, healthcare professionals and medical and academic institutions of all backgrounds hold the joint responsibility of remediating the violation of trust against Black patients in the United States.

Informed consent is an essential pillar in ethical medical research. It requires that all research participants are willing and able to make an informed, voluntary decision to participate in a clinical trial.

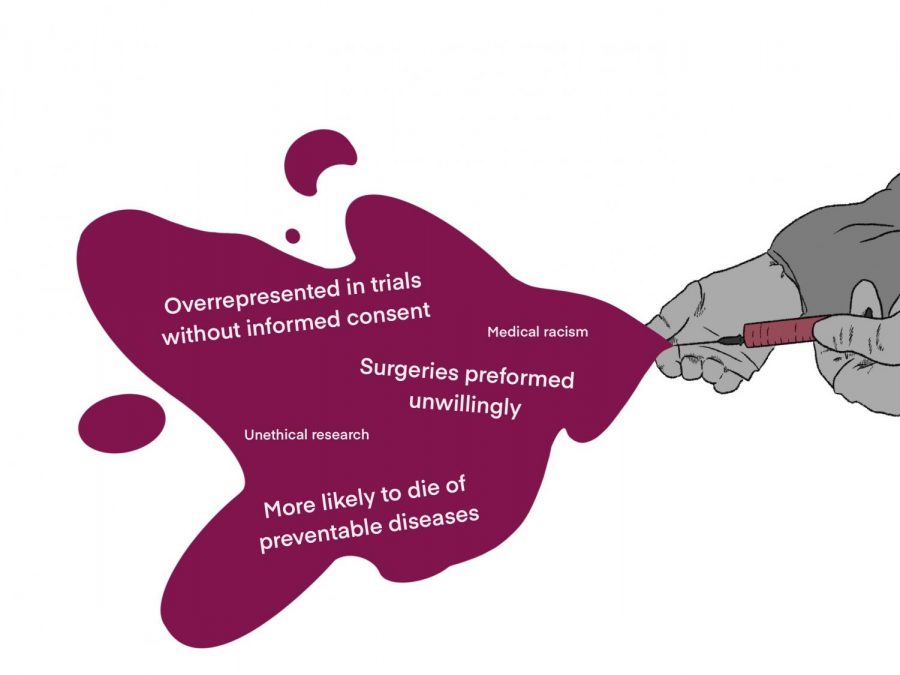

Throughout U.S. history, scientists and clinicians have pushed the boundaries of medical innovation at the expense of Black people’s right to informed consent.

From J. Marion Sims perfecting the vesicovaginal fistula repair on unwillingly Black women in the 19th century to a 2018 study showing that Black patients were overrepresented in clinical trials that were exempt from providing informed consent, the medical field and the non-Black patients it was designed to serve has time and time again shown itself to be a beneficiary of systemic racism.

Research ethics committees like the Institutional Review Board need to be more stringent with the regulation of clinical investigations involving human subjects. Institutions and principal investigators who engage in unethical research practices must face consequences. In addition, tolerance for ethics breaches could be prevented early on by including diversity and ethics training for researchers affiliated with universities and government-funded programs.

Last fall semester, I took a research ethics class along with around twenty other students who did publicly-funded research on campus. We covered the topic of medical racism by reading and discussing Harriet Washington’s Medical Apartheid, as well as weaving the themes of that novel into our later class discussion ethics as it concerned our research projects as well as current ongoing clinical trials for COVID vaccines and therapeutics.

As an undergraduate researcher, learning about the problem of racism in science and medicine alongside my peers who are on track to be the doctors and scientists of tomorrow was a formative experience other undergraduates and early-career scientists can greatly benefit from.

Black people are more likely than people of other races to die from pregnancy-related causes and preventable chronic diseases like heart disease and cancer, and many attribute these differences to racial discrimination. An impactful and commonly proposed solution to properly serving Black patients is to connect them to Black doctors. However, the burden of addressing institutionalized racism in medicine should not fall on Black people alone.

There have been many influential Black doctors over the years who have made important contributions to the medical field as a whole while staunchly advocating for the rights of Black patients: Patricia Era Bath, Marilyn Hughes Gaston, Louis Wade Sullivan, Charles R. Drew, Leonidas Harris Berry, just to name a few.

Despite the contribution of Black professionals in healthcare throughout history, the approximately 45.5 thousand Black physicians in total in the United States are far too underrepresented in medicine to meet the demands of millions of patients who may want providers who look like them. To make matters worse, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) observed that the growth of Black medical applicants, matriculants, and graduates lagged behind other underrepresented people of color.

Increasing diversity in the medical profession requires addressing racism all the way down the educational pipeline from supporting students in their K-12 education to ensuring undergraduates and medical students have adequate resources from mentors who look like them.

Children and high school students need to be exposed to post-secondary education regardless of whether or not their parents went to college. In between standardized tests, managing extracurriculars and college applications, it takes community support and essential volunteer efforts to ensure younger students have diverse role models who can help them get to college and thrive there.

Even when institutions pledge to admit diverse students, that effort is much less valuable when those underrepresented students don’t have the support to thrive in college and beyond. At San Diego State specifically, it’s important that we continue to celebrate and support resources that help Black students, especially those who will be our generation’s health providers and medical researchers. These include the Black Resource Center and the Center for the Advancement of Students in Academia (CASA) and communities like the Black Student Science Organization (BSSO).

While diversity in medicine is instrumental to addressing medical racism, dismantling racial oppression in healthcare requires collaboration from white and non-Black people of color, too.

The hundreds of thousands of active physicians who are white or non-Black people of color have a lot to learn about serving Black communities in culturally competent ways. This extends beyond just understanding the deep history of medical racism.

Doctors and scientists alike must seek to understand the epigenetics of multigenerational stress in Black families. Doctors who are interested in advocacy could focus on how city planning and health policy affect environmental determinants of health, especially in predominantly Black neighborhoods and work directly with politicians and public health officials to support preventive healthcare for underserved groups.

In 2020, Daily Aztec Opinion Editor Trinity Bland wrote a piece discussing how the term “people of color” was dismissive of the differences in experience between Black individuals and other people of color. Those differences as especially apparent in a 2018 Pew Research study that showed Black professionals in STEM were more likely than their Hispanic and Asian counterparts to view workplace diversity as important, to say there is too little attention to workplace diversity and to experience racial discrimination in the workplace.

If we want to tackle systemic medical racism, we cannot treat BIPOC as a monolith and ignore the richness of different cultures and attitudes in concern to wellness.

For those interested in entering the caring professions in particular, the goal of guaranteeing the right of quality healthcare for all can only be achieved through anti-racism. This Black History Month isn’t just a time for celebration and visibility for Black folks, but also a time that everyone can use to reflect, learn and do our part to create a more just world.

Jessica Octavio is a junior studying microbiology.