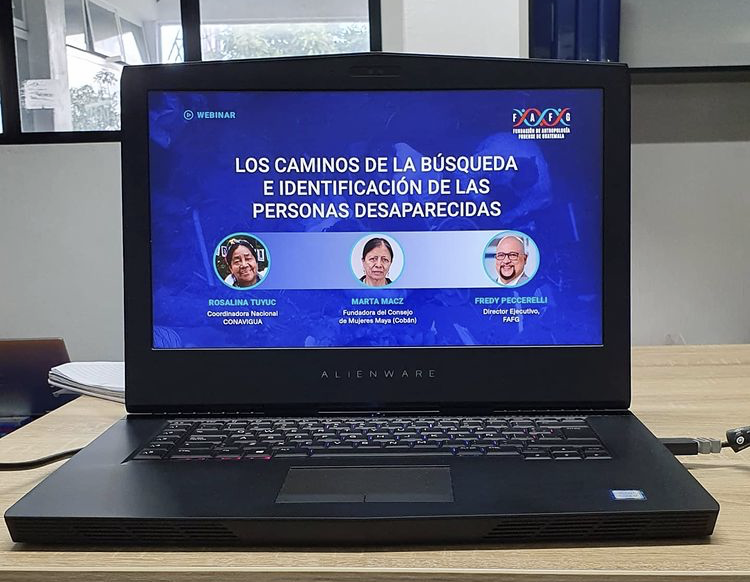

A webinar titled “Pathways for Searching and Identifying the Disappeared” celebrated 24 years of hard work from the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation (FAFG) on Oct. 26.

Some of the event’s guests included Rosalina Tuyuc, Marta Macz, and Freddy Peccerelli. Peccerelli, a forensic anthropologist and executive director at the FAFG, explained the issues in Guatemala more in depth.

“Let’s think that Guatemala is in the middle of an armed conflict which left 200,000 victims, 160,000 of these people killed in massacres and 40,000 of those people missing,” Peccerelli said.

Peccerelli explained that most of the people “missing” were actually just killed and hidden during the Guatemalan Civil War.

“The foundation arose in this space, where women like Rosalina Tuyuc, like lady Marta looking for their family members, looking for support, help,” Peccerelli said. “Someone who knew how to look and that they could trust. Then, they invited Dr. Clyde Snow.”

Peccerelli commented on the relationship he had with Snow, who was his mentor and close friend.

“He taught me perhaps what was most important,” Peccerelli said. “That the work we do is an act of respect to the families. It’s in the act of giving answers to those families.”

Snow is recognized as a forensic anthropologist, and in fact has been mentioned as a legendary detective, according to an article by the New York Times.

The same article mentioned Snow identified John F. Kennedy, the Nazi criminal Josef Mengle, and “the disapperead” in Argentina, amongst other peoples. He testified against Sadam Hussein and inspired a movement centered on using forensic anthropology to help with genocide cases in Kosovo, Bosnia, Rwanda and Chile.

Macz, a Maya Q’eqchi community leader and another featured guest, founded the Council of Mayan Women in the northern region of Cobán, Guatemala. According to the foundation’s website, Macz was the first woman and first indigenous woman candidate for mayor of Cobán.

She said the kidnapping of her brother was what originally inspired Macz to involve herself in humanitarian work.

“[He] worked in cooperatives, that was his sin,” Macz said while visibly tearing up. “The cooperatives stopped existing and many people that worked in the cooperatives also disappeared.”

The search to find her brother led her to hospitals, to the press and to knock on doors in different military zones. Her brother was kidnapped by members of military intelligence from the Guatemalan armed forces.

They didn’t know what could have happened to her brother for 29 years. Macz said she met many “brave” women who had also lost people and they united to find their families.

“In this organization, we were primarily centered with getting the psychological attention that we all needed,” Macz said.

Macz said a lot of the women who formed part of the organization lost their lands and were wandering from one place to another because they had nowhere to go.

In February of 2012, Macz and her group were allowed to look in mass graves used to bury the disappeared close to the military center after many efforts from the forensic anthropologists who participated in the searches with them.

“My brother was face down with a noose made from a military shirt around his neck,” Macz said.

In 2015, she was given the body—which she buried fulfilling a promise she’d made to her parents—before they passed. Macz said she wasn’t counting on the presence of many people at her brother’s funeral service, due to the fear the military-installed. To her surprise, at least 200 people showed up. Macz mentioned finally having a place to put flowers, including for Dia de Los Muertos (Day of The Dead).

“Following a season of solidarity with each other the reports about sexual abuses against women, abuses against families who had members detained/disappeared initiated,” Tuyuc said. “We have the right to look for families, we have the right to demand justice and the right also to beat that fear which stayed behind after 36 years of militarization.”