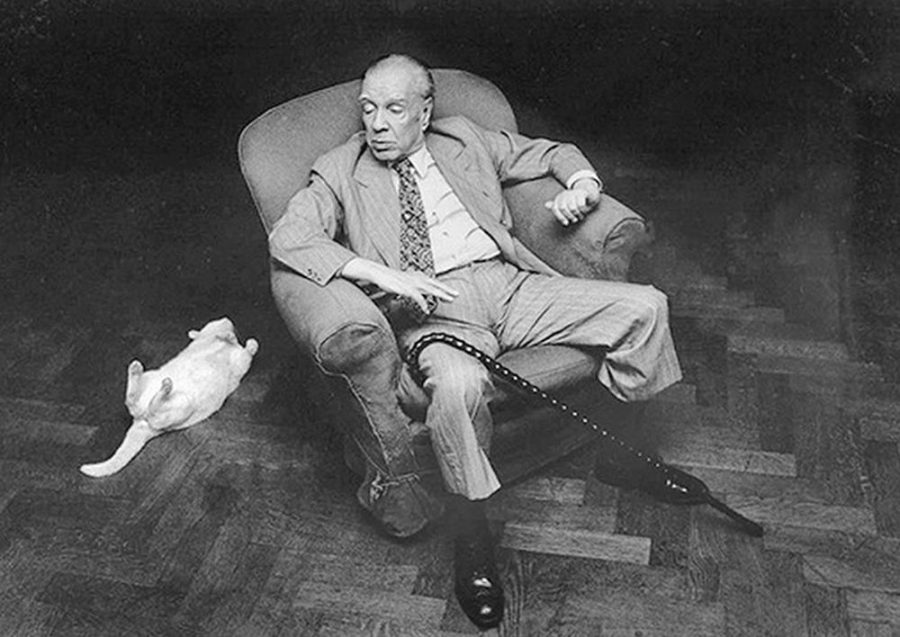

A man searches a universe-sized library that houses all books that ever were written and seemingly, ever will be written. A young Argentian boy has a photographic memory so strong he can live entire life spans within his past that the present ceases to exist. These are just three of the many short stories that belong to the speculative fiction master that is Jorge Luis Borges.

Over the past year, I’ve developed a serious reading habit. Actually, addiction might be a more fitting title. Some 35 books, give or take. This is the most I’ve ever read in a single year before in my entire life and over the course there have been some fantastic books. Whether it be “Blood Meridian” or “Gravity’s Rainbow,” I’ve knocked down some real titans. It wasn’t until the past week or so that I purchased the “Collected Fictions” of Borges that I’ve really come to appreciate not just his writings or what he exemplifies about great story-telling but my new-found hobby as a whole.

I’d call Borges’ works “livable fiction,” that is, a fiction so realistic in its portrayal of fictional cities, places, characters and worlds, lore and history within those characters and worlds. It highlights why we love stories in the first place. It’s a subgenre called “Speculative Fiction.” The genre today is more an umbrella term to house genres like horror, fantasy and sci-fi. Borges’ specific take is more of a means to an end, with a lot of stories delving into the outright fantastical, but it always accumulates in some way to explore the recesses of the human experience.

For example, the very first story of “Ficciones” (the most popular of Borges’ short-story collections and the one I most recommend) is titled “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” involves two individuals initially arguing over “the way one might go about composing a first-person novel whose narrator would omit or distort things and engage in all sorts of contradictions so that a few of the book’s readers – a very few – might divine the horrifying or banal truth.”

Later these two end up going down a rabbit hole to locate the source of the titular country “Uqbar,” its legend of “Tlön,” and the in-world, “real-world organization” “Orbis Tertius.” The entire story is an exercise in comparing the realities of the idealist versus those of the realist. Is there object permanence? How do we know our reality isn’t simply a projection of our minds; are we relegated to the recesses of the minds as solipsists?

This place called “Tlön” is a personification of what reality might look like through the ideas of an idealist. In layman’s terms, imagine trying to describe anything, without nouns, without any pre-existing knowledge of how things were purely based on the experiential. It’s the phrase “take it as it comes” to the extreme. All of this, being started by one of the individuals quoting some mysterious epigram, “mirrors and copulation are abominable, for they multiply the number of mankind.”

It is extremely meta and if you got confused reading my micro summary of this short story, it should explain just how insanely in-depth Borges can be when creating these microcosms of worlds within worlds.

Many of his characters even mirror and personify the confusion of the reader. His books aren’t just books — they’re books about books, stories that examine what stories do to us, why lore and history intrigue us so and what pulls us into a gripping narrative.

These aren’t just themes limited to the paper format, they’re the very ideas that make excellent narratives period. You can find the influence of Borges in literature just as much as you could find it in your favorite TV show, movie, role-playing tabletop or video game. Borges excels at the cerebral, and I’ve never read another author that’s ever achieved this sort of “effect” with their writings.

It is dizzying in the best way possible, and the best part is that Borges’ specialty was all in the short story. The man lives in brevity, expelling the most with the fewest pages possible.

All this is to say that I think he is trying to say something about how humans can conceive and comprehend meaning, and what it can do to teach us about ourselves or what we aspire to be. A common trope in Borges’ works is the inclusion of labyrinths, in all means figurative and literal.

A library can be a labyrinth of knowledge, his stories are about characters that dream of finding their way through labyrinth-like passages, their own dreams chronicling an epic poem their great ancestors wrote, a journey so winding that they find themselves enshrined in a history of labyrinths, or a labyrinth-like history. Life is like a labyrinth, a never-ceasing deluge, one after another of confusing, forking paths.

Dreams are another trope he uses. People dream of lives they once lived, or will live. Dreams become alternate realities that are so analogous to reality, they just outright become one. A character starts to forget whether they dreamed of this life first, or if they’re living in a dream at all. Other common occurrences are philosophers and myths, characters so engrossed in history and the practice of re-living the past that they cease all of their present consciousness.

Reading “Borges” is like volunteering for the most intense meditation session you will ever experience: he gives you the choice to leave reality behind. While that can seem a bit extreme, I’ve found it to be cathartic, especially if you’re someone currently stressed out or are looking for solace in any capacity.

The format of reading, however, is just as important. His writings are the most visceral when physically holding those pages most palpable. Borges’ writing encompasses ideas all housed in healing, life-affirmation, knowledge and metaphysics, the human condition, etc. It is imagination, pure and distilled to its most elemental form. They are, quite simply, the best I’ve read, and being housed in Love Library, they await a reader most eager and sincere.