At the 29th International Astronomical Union General Assembly on August 14, San Diego State astronomy professors William Welsh and Jerome Orosz announced the discovery of the new planet that orbits two stars instead of one — the 10th such planet ever discovered.

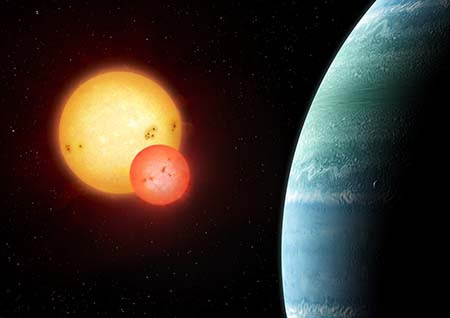

The new planet, called Kepler-453 b, is the third planet to lie in the habitable zone of the two stars it orbits. In other words, it sits in an area where the energy from the stars adjusts the planet’s temperature to a point where liquid water can exist.

To make this discovery, Welsh and Orosz’s team searched for eclipses in data gathered during NASA’s Kepler mission. When they found an eclipse, it indicated there was something blocking that star, potentially a planet.

To the astronomer’s surprise it was a planet, with a radius a little more than six times greater than that of Earth, according to The Astrophysical Journal.

Astronomers were also shocked to find the tilt of the planet’s orbit changes rapidly. It also takes 240 days to orbit its two stars, compared to Earth’s 365 days to orbit the sun.

The change of orientation of the planet’s orbital plane, known as precession, brought it into proper alignment halfway through the space telescope’s lifetime during the Kepler mission, allowing three transits to be observed before the end of the mission.

“The detection was a lucky catch for Kepler,” Welsh said. “Most of the time, transits would not be visible from Earth’s vantage point.”

Transits from Kepler-453 b won’t be visible again for a long time.

“The low probability for witnessing transits means that for every system like Kepler-453 we see, there are likely to be 11 times as many that we don’t see,” Orosz said. “The precession period is estimated to be approximately 103 years. The next set of transits won’t be visible again until the year 2066.”

The discovery confirms such planets are not irregular in the Milky Way galaxy.

“They are not rare, in the sense of how many there are in our galaxy,” Welsh said. “We estimate there are probably 100 million in our galaxy. There are lots of them, they are just hard to find.”

Once, transiting circumbinary planets were considered imaginary, like the fictional planet Tatooine from “Star Wars.”

The project was funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation, and NASA’s Kepler mission allowed for the discovery.

Astronomers can now begin to compare different systems and look for new trends that could point to more of this type of planets. Welsh said the discovery was a collaborative effort and it wouldn’t have been possible without the people he worked with.

“Jerry and I work very closely together, but there are other people in our group that really deserve the credit for all the discoveries,” Welsh said. “And so whenever I get interviewed I also ask that people keep in mind that it’s not just me. There are other folks that also worked very hard on this.”

Although the SDSU astronomy department is small, its research continues to make an impact on the astronomy community.

“The CSU system isn’t as renowned as the UC system when it comes to research, but San Diego State is an astounding university in the CSU system,” Welsh said. “In astronomy, SDSU is definitely on the map. We are some heavy hitters and even though we are a tiny department, we are doing some heavy work, and folks know about San Diego State.”