Shortly after Robin Williams’ suicide, clinical psychologist Michael Friedman offered sobering commentary about the illness that perhaps triggered the tragedy. In an article for CNN, Friedman wrote, “Depression does not discriminate, cannot be bargained with and shows no mercy.” Without trivializing the illness, Friedman touched on a bitter but important truth: While factors such as family history and substance abuse can be primary causes of the complex illness, depression can happen to anyone at anytime and anywhere.

This truth is even more accurate for San Diego State and college campuses. Earlier this April, we found ourselves mourning SDSU engineering freshman Christian Pier Ayala, who died by suicide after drowning in Lake Murray. For many who knew Ayala for his “innate ability to light up a room, bringing life and laughter to those around him,” the means of his death were perhaps shocking. A punctured raft, empty bottle of vodka and suicide note signaled this wasn’t an isolated incident, but a calculated result of an ongoing struggle with depression and suicidal thoughts.

Which leaves us with a realization to confront: The pressing issue of depression and suicide among college students also isn’t isolated, it is systemic. As hundreds of new college freshmen come to SDSU to find their place on campus and experience the “best years of their lives,” they might be unaware they’re part of a demographic that struggles with the highest rates of depression and suicide. After last semester’s tragedy, the SDSU administration needs to make combating college-age depression a priority.

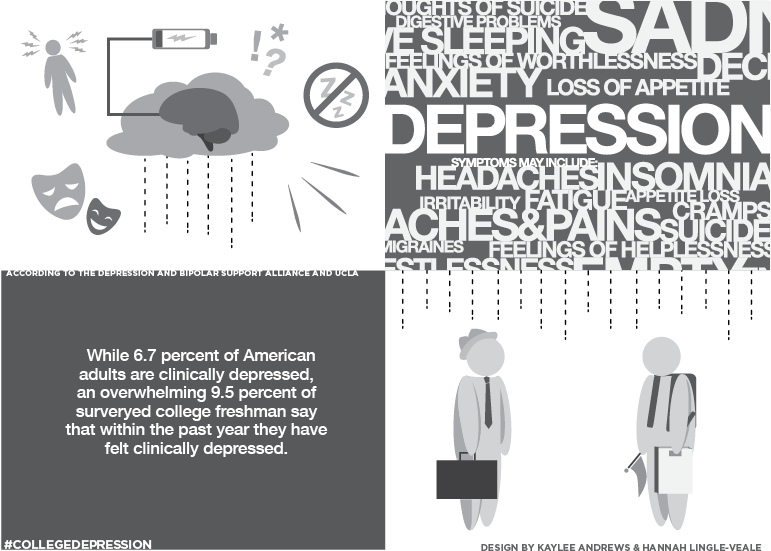

An annual survey conducted by UCLA found incoming freshmen from the 2014-15 school year were the most depressed they’d been since the survey began 49 years ago. According to the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, 6.7 percent of American adults are clinically depressed. But the UCLA study found an overwhelming 9.5 percent of surveyed college freshmen said they felt clinically depressed to the point where it became “impossible to function” in the past year.

The growing rate of depressed college students is becoming a concern for college counseling directors. In a 2013 survey, over 95 percent of college counseling directors said the number of students with significant psychological problems (anxiety leading with 41.6 percent, depression at 36.4 percent) was a growing issue. Perhaps, it is also no coincidence suicide has become the second-most common killer of college students, according to suicide.org, and suicide rates among college students have nearly doubled since the 1950s.

This rise in college-student depression can be attributed to many factors, according to the American College Health Association: situational anxiety, stress about school, helicopter parenting, finances, social anxiety and new environments. Recession-era millennials who enter college aware of rising graduate unemployment and crushing post-grad debt can experience depression through what American psychologist Rollo May would say is “the inability to construct a future.”

However, despite this pervasive issue, depressed college students aren’t getting the help they need primarily because of two reasons: inadequate, overburdened mental health facilities on college campuses, and a negative social stigma associated with mental illness. This social stigma was made all too apparent when Fox News host Shepard Smith (who has since apologized) called Robin Williams a “coward” for resorting to suicide after struggling with depression. Claims that depression is as curable as the common cold and is simply a result of “being in a funk” add to the stigma of depression in college.

But, depression isn’t as trivial as it might sound. Depression is not simply the state of being “depressed,” it is a legitimate debilitating mood disorder. Much like how physical disorders handicap a person’s physical abilities, depression limits a person’s ability to function mentally.

Unfortunately, this stigma is also being perpetuated on the administrative level. High-profile cases of students being barred from Yale, UC-Santa Barbara, Northwestern and Princeton after their depression surfaced confirm students’ fears that their mental illness could get them kicked out of school. When Rachel Williams sought help from Yale after having depression and harming herself, she was forced to withdraw from school, according to an account she wrote for Yale’s campus newspaper. Williams’ story isn’t unique. Over 62 percent of students that withdraw from college do so because of mental health issues, per a survey released by the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

These incidents and Ayala’s death beg an honest reckoning from us as a community about what can and should be done when combating college depression and suicide. As a school, we can and must do better for each other. Ayala’s death could have been prevented. While students are made aware of the available counseling services, admitting that one has depression is hard to do on one’s own. Maybe acknowledging how common it is among college students would normalize the process of seeking help.

Perhaps the best we as students can do is stop being bystanders. Stephen Fry, an English comedian who has publicly spoken about his depression, said, “If you know someone who’s depressed, please resolve never to ask them why. Try to understand the blackness, lethargy, hopelessness, and loneliness they’re going through. Be there for them when they come through other side. It’s hard to be a friend to someone who’s depressed, but it is one of the kindest, noblest and best things you will ever do.”

The question of depression isn’t concerned with how or why it happened, but how we can be better, do better and move forward for each other.