San Diego State University’s Honor 113 section on Borders, Migration and Detention in the Americas, taught by Professor Kate Swanson, has spent the spring 2021 semester studying conditions at the U.S./Mexico border.

As a function of this course students read and respond to letters from migrants currently in detention, primarily in Louisiana and Texas. These letters are exchanged in collaboration with Haitian Bridge Alliance and the Alliance in Defense of Black Immigrants.

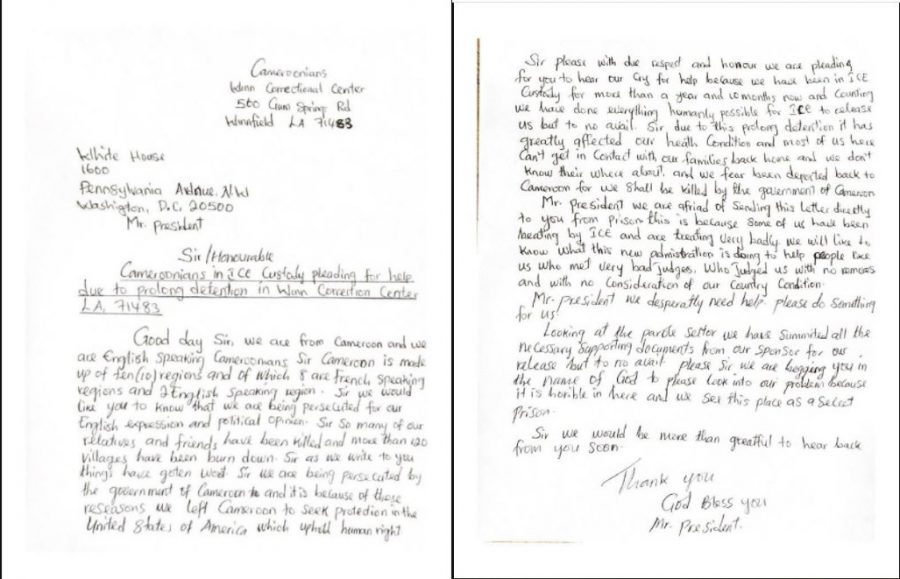

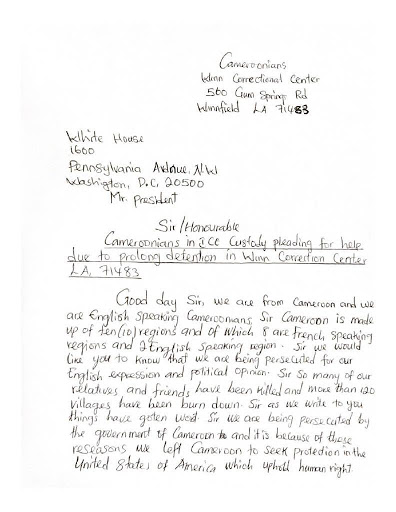

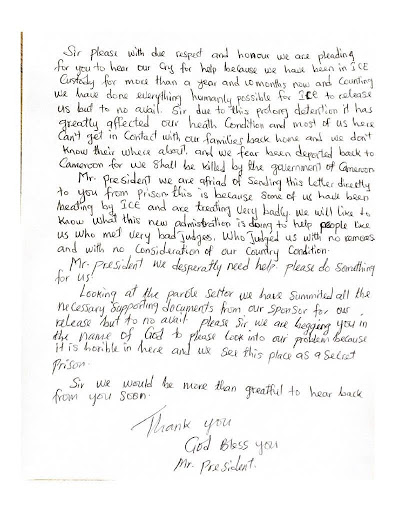

Pictured below is one of those letters. Addressed to President Joe Biden, it was sent by Cameroonian asylum seekers to Alliance member Dr. Anne-Marie Debbané. It is shared here with her permission.

The Letter to President Biden

This letter is one of many received by the course that details conditions faced by migrants in ICE detention. The asylum seekers writing in the letter above fled Cameroon for fear of governmental persecution.

Leaving Cameroon

The West African country of Cameroon has been heavily impacted by colonialism over the last two centuries. The region has been occupied at different points by the governments of Germany, Britain and France, but Cameroon has been recognized as an independent sovereign state since the early 1960s.

The turmoil facing the country today can be tied back to its history of colonization as modern civil tensions fall mainly between the Anglophone and Francophone populations – the two former English and French colonies, respectively. In an attempt to combat the rising separatist sentiment of recent years, the French-speaking majority government has continually and violently persecuted the English-speaking minority population. In response to this persecution, extreme separatists from the English-speaking minority have begun to retaliate in similarly violent ways but on a much smaller scale.

Governmental persecution in Cameroon has been heavily documented, and many of the letters received from immigrant detention describe life in Cameroon as a “living hell.”

As a result of this violence many Cameroonian individuals, mostly from the country’s Anglophone region, choose to or are forced to leave Cameroon in search of asylum in the United States.

The Migrants and Their Journeys

Note that the following excerpts from migrant letters from detention have not been edited for clarity, except to ensure the migrants’ safety. For most of these individuals, English is one of many languages that they are able to speak. The Anglophone region of Cameroon speaks Kamtok or Cameroonian Pidgin English. These quotes have been transcribed from handwritten letters. All of the following individuals are seeking asylum in the United States.

To provide more context to the horrific conditions that migrants often endure and to combat the dehumanization that they often face in the media, the following are quotes from their own letters that would not normally be printed, as they don’t detail pertinent legal or humanitarian information.

In a letter to one of the course’s students, one asylum seeker writes, “I am a calm person and I love to put people’s interest before mine. That is I care about my friends and family a lot. I like listening to musics and watching movies, but my best thing is watching foutboul. I also love eating but am not fat. I love our Cameroonian meals. e.g. “Eru.” I have a bachelor degree.”

In a separate letter another writes, “I am a very good cook and I eat all type of food and my favorite food is (fufu and eru). Talking about music I listen to all types but my best is Gospel, Hi-pop and rap.”

“I had a Bachelor’s Degree,” another writes. “I love watching soccer which I do play very well, I watch African movies that Depict African Culture and I love listening to news. Cameroon has more than 250 ethnic groups each having it’s own native language different from others.”

Another asylum seeker writes, “I hope you, your love ones, and team men are doing great along with the plight of this outbreak. I greatly appreciate your concerns especially the time you put in responding all my mails.”

One migrant writes in farewell, “Be safe, wear a mask and keep the distance.”

Many migrants also talk about their spouses, children, parents, and other relationships in their letters; this information was omitted for their own safety.

The same asylum seekers repeatedly recount the grueling, and often traumatizing, journey they must take to reach the United States border.

One of the migrants from above writes: “My trip to the US was very complicated, bad I saw a lot of things that would never escape my mind. I left Cameroon by flight to Equador, from there I took a bus to Colombia, from Colombia to Panama Deadly Jungle were I saw skeletons of people who died air long, Dead bodies of young men and girls, pregnant women. Some died with babies on their back due to lack of food in the Panamian Jungle which is one of the Deadliest In the world, due to poisonous snakes, scorpions, spider, poisonous frogs, nothing to eat except sugar we had to put in containers and carry water which is composed of dead bodies to drink so as to have energy to stay alive. I thank God for his grace upon my life.”

For Cameroonian asylum seekers, this type of journey is common. It is one of the only ways they are able to get to the United States from the West African country.

Seeking Asylum

It is important to note that the process of seeking asylum in the United States is a fully legal endeavor and that the individuals who ask for it are operating within existing legal frameworks.

Once a migrant passes a Credible Fear Screening, designed to gauge how afraid they are of returning to their home country, they are placed in immigration detention somewhere in the United States – not necessarily at or near the border. Many of the migrants corresponded with in Professor Swanson’s section of HONOR 113 are placed in Louisiana and Texas.

Many asylum seekers, like those in the letter above, refer to immigration detention as a “secret prison.” Seeing as ICE rents beds from existing private prisons to house their detainees, this is a chillingly apt description.

One migrant writes the following on the medical attention available to them from their facility:

“Deplorable medical attention, we are in a facility where, for numerous and different complaints laid, Ibuprofen is the sole medicine given, just for the sake of not letting patients go without medication based on complaint…Everyday at the facility, we keep on having new intakes from different detention centers and some of which are been caught by ICE on street and others by the CBP…We were all forced to sign a form labelled N-95 masks to proof that the facility issues us the aformention mask of which we are not being issued…We have observe[d] with fear the poor management of PPE (like face mask) by health workers and officers in the facility especially after attending to dorms housing Covid-19 positive detainees.”

In that same letter the migrant writes, regarding the aftermath of an attempted hunger strike, “Some other detainees from other nationalities started another hunger strike requesting for release or deportation … but in response, they were pepper sprayed and locked up in solitary confinement for about 2 months each.”

Similar claims of being forced to sign documentation have been reported by The Guardian here.

Similar claims of medical negligence and poor treatment in ICE facilities have been reported by The Guardian here.

Beyond this migrants face another challenge, one detailed in the letter to President Biden above: they do not know when they will be released from detention, either to the United States or to their country of origin. In their letters, migrants express fear and confusion as to how long they will have to stay in immigration detention. Many of the asylum seekers that students in the course corresponded with have been in detention for over a year, and are being held indefinitely.

“I came here to the United States to seek for protection because of the persecution I faced back in Cameroon,” another migrant writes, in a separate letter. “but instead I became a prisoner.”

Interviews from the HONOR 113 Course

Professor Swanson, who has spent much of the last decade working in migrant rights, notes that the letters she received from detention at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic detailed especially dire conditions.

“From 2018 until last semester everything was pretty consistent,” she said. “[But] when the Covid crisis hit the letters got really dire because we started hearing more about people who were getting Covid, who were terrified that they couldn’t get released, about the mistreatment and medical neglect at the hands of ICE and CoreCivic and GEO Group, private prison institutions.”

Swanson also said many migrants had been sent back to their countries of origin in recent months, especially Black Africans and Haitians. According to Swanson, these individuals were deported back to their home countries in large numbers around November. Swanson went on to note that activist groups have been working hard to combat this, including the Haitian Bridge Alliance and the Alliance in Defense of Black Immigrants.

When asked about how migrants’ stories are portrayed in the media, Professor Swanson says, “Sometimes we can tend to victimize [migrants], so I think it’s important when writing about these issues to use their words. They can speak for themselves and really show their agency and [fight] back against this unjust system … as best they’re able to.”

On the importance of letter writing, Swanson says, “I feel like writing letters to individuals within immigration detention is an excellent way for people to connect with the individuals behind the numbers, to hear their stories, to humanize their stories, to find connections across our shared humanity. In doing so I’m hopeful we can build more empathy, and be more motivated to take action.”

Sarah O’Toole, a sophomore International Security and Conflict Resolution (ISCOR) major and honors minor at SDSU, describes her participation in the class as incredibly impactful.

“This class has encouraged me to try and uproot the system through activism and offer as much humanitarian support to migrants as I can,” O’Toole said. “It was an amazing honor to be able to do this…I learned so much throughout this process and I highly recommend letter-writing to anyone who is interested.”

The Future for Migrants in Detention

For migrants currently in detention, there is a small light of hope: despite facing mass deportations during the final months of the Trump Administration, many individuals are now being released from ICE detention to await their cases inside the United States. Swanson notes that the migrants are still not free – they are required to “wear ankle monitors, undergo surveillance, and report in” – but they are out of detention.

This new policy, and the Biden Administration’s stated commitment to immigration reform, point to a more humane future for migrants currently in immigration detention. It’s important to note, however, that the Biden Administration still has not rolled back Title 42, a Trump-era policy that closed the southern border to asylum seekers in an attempt to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

Despite the odds stacked against them, one migrant remains hopeful:

“the[re] is more to talk about my country, my journey and this detention in which I fine myself,”

one asylum seeker writes, “but it will be better when I am out of here.”

For more information on the United States detention system or to get more involved in migrant rights, further resources include the following organizations: Haitian Bridge Alliance, Alliance in Defense of Black Immigrants, Al Otro Lado, Detention Resistance, Jewish Family Services, Poetic Justice, and Border Angels. SDSU has its own on-campus chapter of Border Angels, which can be contacted via their Instagram @borderangelssdsu.

The Alliance in Defense of Black Immigrants was titled incorrectly in an earlier publishing of this article.