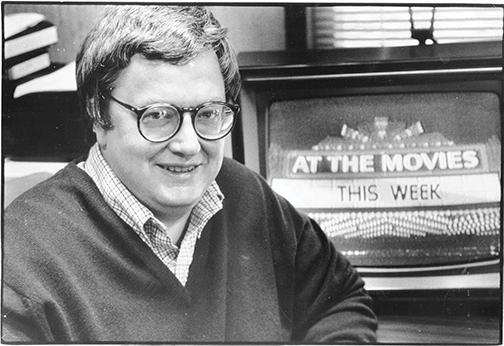

My favorite review of Pulitzer-prize winning Roger Ebert’s is his last one.

Ebert reviewed Terrance Malick’s “To the Wonder,” an obscure romance movie which was critically panned as being overwhelmingly somber and stylistically disastrous. The film had a less than favorable score from multiple film critics. Ebert had enough evidence from his colleagues and the public that the movie was going to be a critical and financial disaster. I thought that Ebert would hate it.

Instead, he surprised me. He praised the film as a beautiful film that escaped explanation and gave it three and a half stars out of four. What was amazing about the review wasn’t how many stars he gave the film, but his writing. He asked an important question, a question that should be asked when it comes to modern day film criticism,

“Why must a film explain everything? Why must every motivation be spelled out?”

At its core, modern day film criticism, as seen on Rotten Tomatoes, the A.V. Club and other blogging and video outlets, assigns value to films based on these objective checkpoints looks down on readers and filmmakers equally.

It’s absurd to critique a film objectively when film as a medium affects moviegoers personally and subjectively.

What is revolutionary about Ebert’s perspective as a film critic is his acknowledgement of his shortcomings as someone who assigns value to an artist’s work. Who is anyone to assign value to something that he or she can’t fully understand, because it doesn’t originate from his or her world? You may not understand a film but you can’t deny it if it makes you feel something.

Granted there are films that are stupid, as there are films that are smart, but to dismiss films that one doesn’t understand as bad is another thing.

Another film review where Ebert articulates this sentiment is his review of the critically panned, “Cloud Atlas.” The complex film interweaves six different storylines into a single narrative. It was criticized as being overly long, complicated and pretentious.

I loved the film because it wasn’t a movie one could explain. Its core ideas transcended what people viewed as a traditional film narrative. I loved Ebert’s review even more because he understood that films couldn’t be explained but simply experienced.

“On my second viewing, I gave up any attempt to work out the logical connections between segments, stories and characters,” Ebert said. “What was important is that I set my mind free to play. Clouds do not really look like camels or sailing ships or castles in the sky. They are simply a natural process at work. So too, perhaps, are our lives. Because we have minds and clouds do not, we desire freedom. That is the shape the characters in ‘Cloud Atlas’ take and how they attempt to direct our thoughts. Any concrete, factual attempt to nail the film down to cold fact, to tell you what it ‘means,’ is as pointless as trying to build a clockwork orange.”

It’s important to remember Ebert as a critic, but even more as a writer, whose words were few but nonetheless impactful and human. That’s how he elevated film criticism, not because of his critiques, but because of his poetic writing.

I never knew Roger Ebert personally, but I miss his presence deeply. I read his work hoping to understand how he could write reviews that were critical yet incredibly human. Perhaps the fact that he could write so humanly and honestly shows self-reflection on his part regarding his own imperfections. There are great film critics who are masters of the form, but there will never be a critic who transcended the role of film criticism like Ebert has.

Film criticism today is all about assigning grades (as A.V. Club does) or percentage of critical acclaim (as Rotten Tomatoes does), but it should be more than just an objective number. Films are made from a personal perspective; therefore their critiques should be subjective and personally resonant.

The writers and editors at RogerEbert.com carry on Ebert’s legacy of personal and thoughtful film criticism, where it becomes less about how many stars a movie gets and more about the words. I enjoyed its review of “Boyhood,” detailing the fleeting nature of time, and the review of “Dawn of the Planet of the Apes,” a review which saw the real-life reflections of war tragedies. However, none will replace the distinctive voice in film criticism that was Ebert.

Roger Ebert passed away April 4, 2013.

When people who have a substantial influence like that pass, they don’t really leave. Ebert lives in film critics across the world. He lives in the writers that have carried on RogerEbert.com and he lives in the film writers here at The Daily Aztec. He is alive where writers exist.